Fieldwork Monitoring in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)

Malter, F. (2013). Fieldwork Monitoring in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. Retrieved from https://surveyinsights.org/?p=1974

© the authors 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

Abstract

The article summarizes how monitoring of fieldwork was conducted in the fourth wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) by using the conceptual framework of total survey error as a guiding principle. I describe the technological and governance-related background of monitoring and managing fieldwork in a tiered principal-agent environment of a cross-national, longitudinal survey operation. Findings on selected indicators are presented as they were utilized in fortnightly reports to contracted survey agencies during the entire data collection period. Reporting was intended to stimulate corrective action by contracted for-profit survey businesses. I summarize our experience of trying to influence an on-going cross-cultural data collection operation and discuss implications for survey management with an emphasis on multi-national surveys.

Keywords

CAPI, data quality, face-to-face, fieldwork, keystroke data, monitoring, panel, paradata, survey management, total survey error, unit nonresponse

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank Markus Kotte, Gregor Sand, Maria Petrova, Johanna Bristle, Barbara Schaan and Thorsten Kneip for their valuable input and help.

Copyright

© the authors 2014. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

1. Introduction

In any survey enterprise, ensuring data quality is a key concern (Lyberg & Biemer, 2008; Koch et al. 2009). Data quality of a survey has many facets which are most comprehensively conceptualized in the Total Survey Error (TSE) approach (Groves & Lyberg, 2010). This article describes how fieldwork monitoring – informed by the two key components of TSE, representation and measurement (Lepkowski & Couper, 2002) – was conducted during the fourth wave of the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE). SHARE is a multidisciplinary and cross-national panel survey with modules on health, socio-economic status, and social and family networks. At the time of writing (March 2013), more than 85,000 individuals from 18 European countries and Israel aged 50 or over were interviewed over four waves.

Fieldwork monitoring comprised a set of activities aimed at minimizing selected components of the TSE while data collection was still on-going and corrective action was still possible. It is one of the many activities over the life cycle of a survey that can have a real impact on total survey error (Koch et al. 2009). Details on TSE can be found elsewhere (e.g. Groves & Lyberg, 2010). I will focus here less on the conceptual details but more on putting the concept into action in a large survey operation.

Given constraint resources, international survey operations may not be able to pay the same attention to each possible error source specified by TSE but may be forced to prioritize, be it for political, methodological, financial and/or human resource reasons. Errors or biases in survey statistics resulting from the misrepresentation of the target population – such as coverage error, sampling error or nonresponse error – make up the first of the two classes of the TSE. In SHARE, like in many other longitudinal studies, we made minimizing unit nonresponse our primary concern due to its quite unfavorable consequences for panel studies (Watson & Wooden, 2009). Unit non-response, be it from lack of locating the respondent, lack of establishing contact or lacking willingness to cooperate (Lepkowski & Couper, 2002) is the main cause of attrition in panel samples. The same factors also influence low response rates in refreshment samples, albeit to a different degree (Lepkowski & Couper, 2002). During SHARE wave four, we focused fieldwork monitoring on activities aimed at minimizing the following three causes of unit non-response a) difficulty of contacting households, b) gaining respondent cooperation, and c) dealing with cases of initial refusal. These activities all contribute to minimizing representational aspects of the TSE.

A second set of monitoring activities was geared at reducing the second class of TSE errors, namely measurement errors (or even bias). One obvious source results from failure to conduct standardized interviewing. More specifically, we focused on the undesired interviewer behavior of not reading question texts properly.

In SHARE, an added layer of complexity resulted from the fact that most countries contract for-profit survey agencies to conduct fieldwork and manage interviewers, not unlike the ESS (Koch et al., 2009). The role of the central coordination team of SHARE at the Max-Planck-Institute for Social Law and Social Policy in Munich was thus to inform the contracted businesses and scientific country teams on a number of relevant indicators of fieldwork progress and data quality. Most representational indicators (i.e. those on unit nonresponse) were set out as quality targets in the specifications of the model contract. Details on these contractually binding standards can be found in the respective sections below. Feedback to survey agencies on these indicators was intended to stimulate corrective action, i.e. make agency managers relay these findings to interviewers. The hope was that making interviewers aware of their being monitored would guide their behavior towards more successful and proper interviewing.

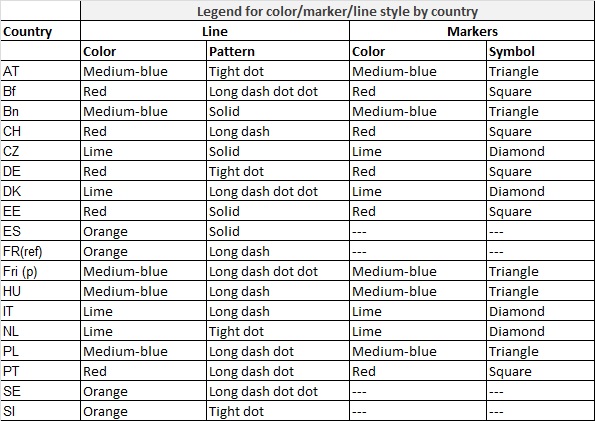

This article is structured as follows: the article starts with an overview of the technology that enabled us to do high-frequency fieldwork monitoring, then continues with an overview about the actual fieldwork timetable of the fourth wave. The core of the article is a brief collection of all indicators reported during data collection. I conclude the article with a summary laying out remaining issues, generalizability of our approach and lessons learned from it for other survey operations and a careful, suggestive assessment of the effectiveness of our attempts to ensure high quality data collection. Note that in graphs I refer to countries with their ISO 3166 codes (slightly adapted for Belgium and France, see chapter 3).

2. SHARE survey technology

All eighteen countries collecting data during SHARE wave four used the same standardized electronic contact protocol, the Sample Management System (SMS). The SMS was installed on every interviewer laptop. It was designed in an iterative process since wave one and enabled interviewers to manage their assigned households (details about the evolution and functionality of this software can be found elsewhere, e.g. (Das et al., 2011). Briefly, the SMS application on a laptop contains all households to be interviewed by a specific interviewer. It allowed the interviewer to record the entire contact sequence from first attempts to completed interview. All contact attempts and contacts were supposed to be entered into the SMS by interviewers, using predefined result codes.

After the composition of the household was assessed per SMS, the actual interview software started. The Computer-Assisted Personal Interviewing (CAPI) software that stores the interview responses was implemented using Blaise code and contained a functionality of logging keystrokes, generating a rich set of paradata where the response time to individual survey items could be computed. These keystroke data allowed the assessment of critical indicators of proper interviewing, such as overall length of interviews, length of modules or individual items (broken down by countries, sample types or interviewer, depending on the purpose). Longer introduction texts were implemented as separate items with separate time logs. Thus, average length of reading these longer texts was compared to the “normative” length of reading the same texts.

Data recorded by the SMS-CAPI application was then synchronized with servers of the survey agency. The software that collects synchronized data from interviewer laptops and contains all households of a country is called the Sample Distributor (SD). It was used – among other things – by survey agency administrators to assign households to interviewer laptops. All laptop data that was synchronized with the agency SD at specified dates was then sent to Centerdata servers. After the first step of processing at Centerdata, SHARE central coordination received interview, SMS- and keystroke data on a fortnightly basis. All dates of data transmission from agency servers to Centerdata servers were fixed before fieldwork started to ensure a synchronized availability of fieldwork data. The central fieldwork monitoring team then combined data of all countries and generated reports that were sent to all country teams and contracted survey agencies. Overall, we sent out 11 reports. In these reports, the current state of fieldwork and relevant statistics on fieldwork progress and integrity of data collection were laid out. Specific problems were pointed out with suggested solutions. This represented a unique feature of the SHARE data collection effort: data on the state of fieldwork is available with high frequency.

3. Fieldwork period of the fourth SHARE wave

Most countries of SHARE wave four had a refreshment sample in addition to their panel sample: Austria, Belgium, Switzerland, Czech Republic, Denmark, Spain, France (in graphs, FRi refers to the panel part, and FRg refers to the refreshment part), Italy and the Netherlands. Belgium was counted as two countries, with a French-speaking (in graphs noted as BE_fr or Bf) and Dutch-speaking part (in graphs noted as BE_nl or Bn). Countries with a panel sample only were Germany, Poland and Sweden. Further, four countries joined SHARE in the fourth wave. Accordingly, they did baseline interviews only: Estonia, Hungary, Portugal, and Slovenia. Israel and Greece, two previous SHARE countries, were not part of wave four.

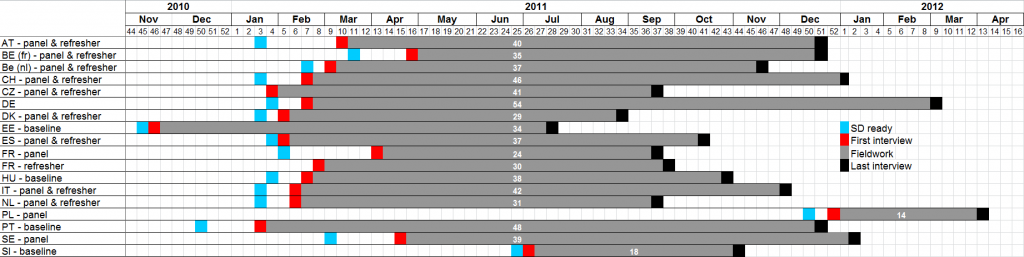

The largest challenge to conduct standardized, harmonized monitoring and management of fieldwork in wave four was the highly asynchronous fieldwork periods between countries. This was largely a result of decentralized funding and associated delays in the start of fieldwork. As can be seen in Figure 1, the most extreme case was Poland which only secured funding for wave four in December 2011. By the time first interviews were conducted in Poland, Estonia had already completed fieldwork six months earlier. Figure 9.1 contains the most important “milestones to be passed” to get SHARE fieldwork underway. From the respondents’ point of view, however, the first encounter with each SHARE wave happens through an advance letter, sent prior to any contact attempts by actual interviewers.

The technological pre-requisite for survey agencies to start fieldwork is the availability of the Sample Distributor software that contains all households of the longitudinal and refreshment gross samples (highlighted blue). This tool was installed on servers of the survey agency and was used to assign a set of households to an interviewer laptop. The next milestone was the first complete interview. The time lapse between receiving the SD and conducting the first interview is spent with setting up the SD software, assigning households to laptops and interviewers contacting households. Obviously, the last interview date (black highlighted) signals the end of fieldwork. The time between first interview and last interview was considered the fieldwork period (highlighted grey). The number of weeks of fieldwork is given by the white number. Germany needed the most time (54 weeks) and Poland was quickest (14 weeks).

Figure 1. Fieldwork periods of all countries participating in SHARE wave 4

4. Indicators of fieldwork monitoring

Most indicators reported in the following sections were part of each fortnightly report. Depending on the stage of fieldwork (“just started”, “advanced”, “almost done”), indicators relevant at that stage were included. Here again, asynchronous timing of fieldwork periods made some information more relevant in some countries than others because by the time country X was in an advanced stage of fieldwork, country Y might have just started. For some indicators, their choice was driven by their continuous relevance to assess progress of fieldwork. Wherever possible, the arithmetic underlying the indicators was derived from the Standard Definitions provided by AAPOR (AAPOR, 2011). Computational details can be found in the methodological documentation of SHARE wave 4 (Malter & Börsch-Supan, 2013). Those indicators were carried forward from one reporting period to the next. In essence, after fieldwork these indicators became the final outcome rates reported for every survey. Some other indicators were only assessed once and reported back to survey agencies in order to highlight areas of improvement, such as read-out length of “wordy” items. Note that all reported statistics are purely descriptive. The goal of fieldwork monitoring was not to explain between-country variation.

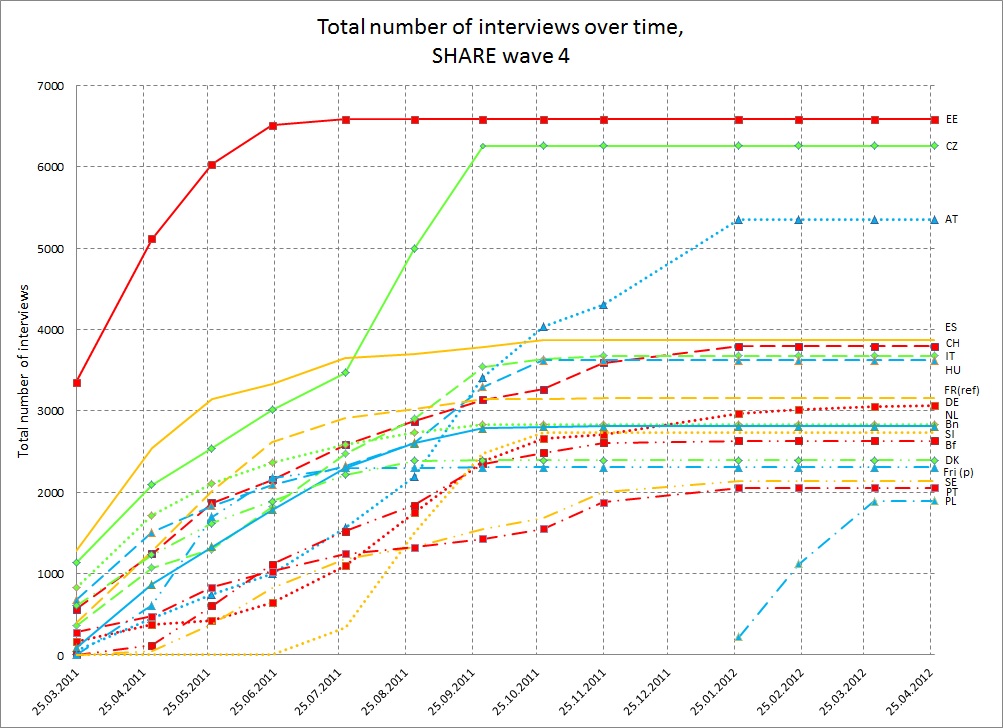

4.1 Total number of interviews

Figure 2 below shows the progress in absolute number of interviews over the entire fieldwork period. In general, each cross-sectional net respondent sample size should be 6.000 but in reality, absolute sample size is dependent – among other things as response rates etc. – on national funding. Countries differed markedly in their slopes. Some gathered high numbers of interviews over a fairly short period of time (such as EE, PL and SI), whereas others took a long time to accumulate a substantial number of interviews (such as DE, PT, SE).

Figure 2. Progress in absolute number of interviews over the entire fieldwork period

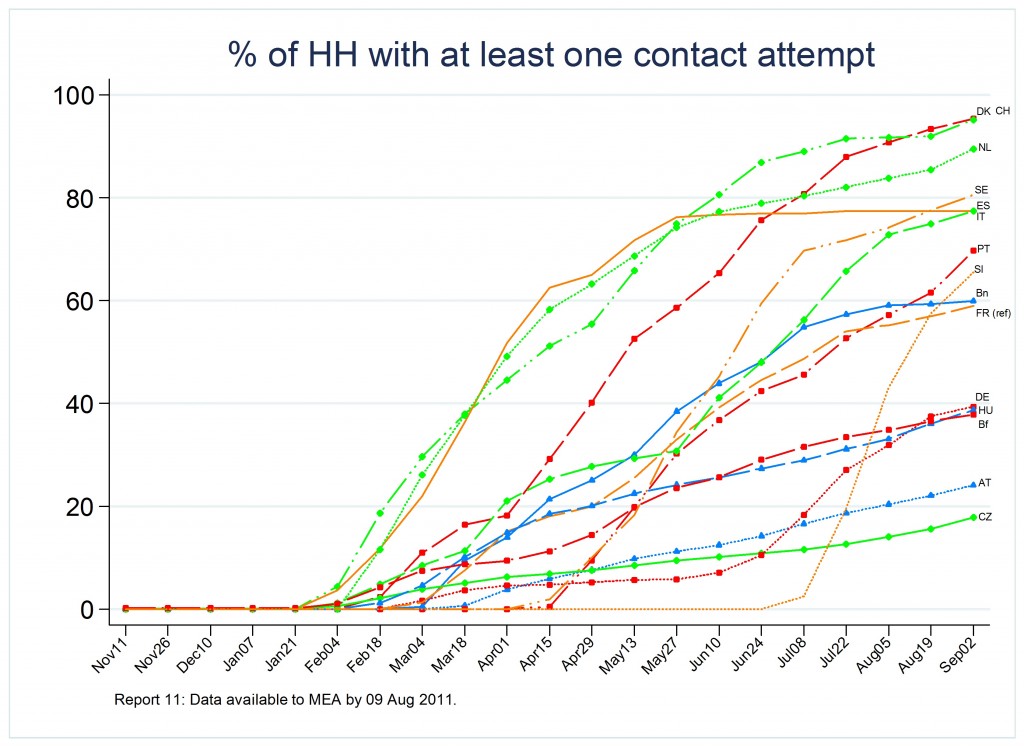

4.2 Contacting households

Attempting to contact households was the first action any interviewer had to do after advance letters had been sent to all prospective respondents in the gross sample. SHARE fieldwork procedures stipulate that first contacts be made in-person. This rule is being followed in all countries exceot Sweden where geographical dispersion of the population makes this approach cost prohibitive. Instead, Sweden is allowed to conduct first contacts by telephone. The rate of gross sample households that were actually contacted is one of the two logical ceilings of final response/retention rates. Cooperation rates represent the second set of logical ceilings to final response/retention rates. As can be seen in Figure 3, countries differed in their strategies of contacting households. Some countries had very steep increases from the get-go, whereas others only very gradually increased their contact attempts.

Figure 3. Rate of households with at least one contact attempt

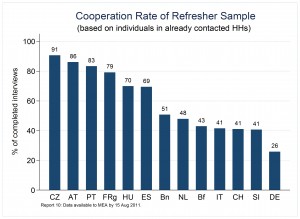

4.3 Gaining cooperation

Once contact has been established, obtaining respondent cooperation is the next challenge to be overcome by interviewers. Figure 4 below shows conditional cooperation rates, i.e. based on those individuals that resided in already contacted households. The number served as a first indication of the general strategy of the survey agencies. Low rates suggested a high number of contacts over a relatively low number of complete interviews. This indicator could not be carried forward in a straightforward graphical manner because a change of this rate could have resulted from an increase in contacts (denominator), complete interviews (numerator) or both.

Figure 4. Conditional cooperation rates of wave 4 refreshment samples

4.4 Refusals

Refusing survey participation was the main source of nonresponse in SHARE. Overall, a lack of interest or disapproval of surveys was the most prevalent in all countries. Other options for interviewers to code refusals were lack of time, too old or bad health and “other” all of which were used by interviewers to a much lesser degree. When we provided this information to survey agencies, we pointed out different strategies of re-approaching households dependent on their refusal reason.

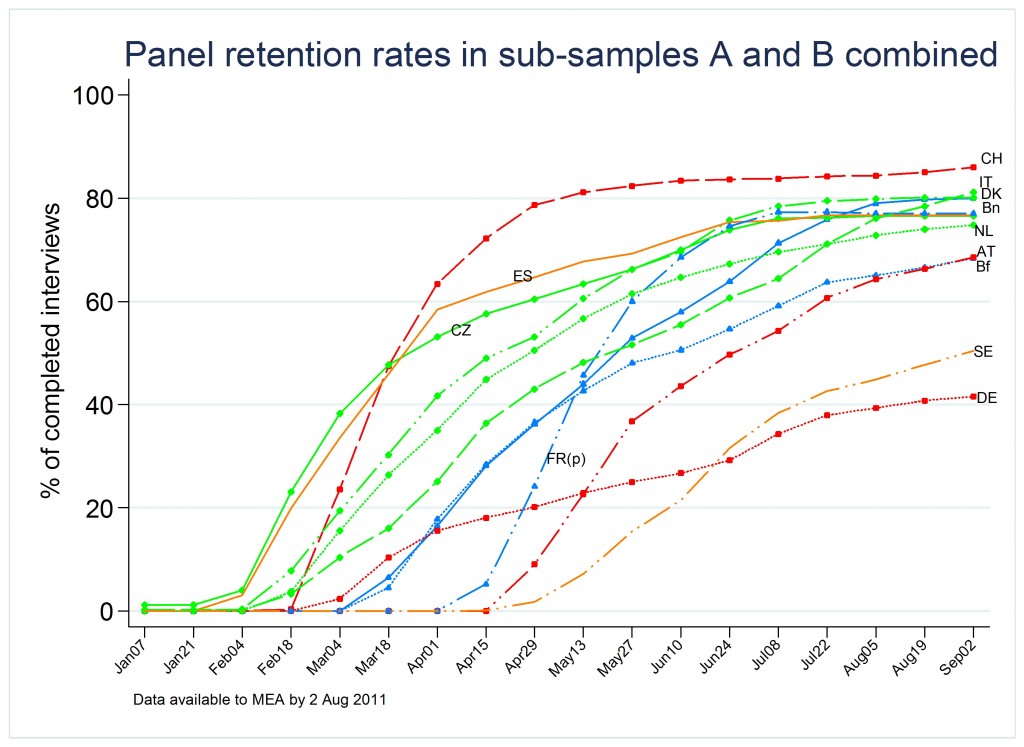

4.5 Panel retention rates

In SHARE, special emphasis was put on respondents who participated in the previous wave (“sub-sample A”) and respondents who have not participated themselves in the previous wave but lived in a household where their partner had participated in the previous wave (“sub-sample B”). A minimum retention rate in the two subsamples combined was contractually set to 80 percent. The snapshot in Figure 5 shows different trajectories of approaching the minimum. Some survey agencies collected interviews very quickly as indicated by steep slopes (e.g. CH or FR) while others made barely any progress at all over the time displayed in Figure 5 (DE).

Figure 5. Panel retention rates in sub-samples A and B combined

4.6 Active interviewers

Duration of fieldwork (expressed in weeks) was dependent on roughly six parameters:

a) Gross sample size (number of households to be contacted),

b) Expected response and/or retention rates

c) Total number of interviews to be conducted (which equals the net sample size of respondents, calculated by multiplying the gross sample size by the expected response/retention rates)

d) Average number of interviewers per week actively working for SHARE

e) Average number of households with a final contact status per interviewer per week

f) Average number of interviews per interviewer per week

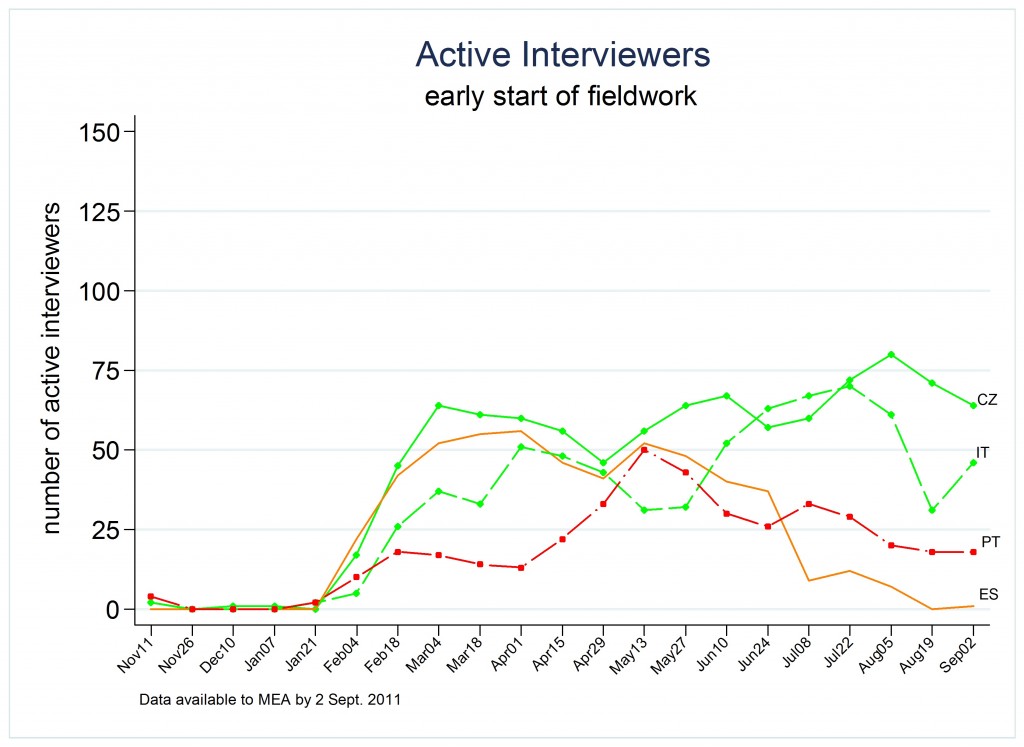

The higher the average number of active interviewers, the sooner a fieldwork is complete. Any survey benefits from a consistently high number of active interviewers, as dragging on fieldwork for too long reduces the chance of obtaining interviews. This has many reasons. For example, interviewers get a routine in conducting a specific interview and lose this routine if they take longer breaks from a specific study to work on other studies. Another reason is that all advance letters may be sent out at once. A long time between receiving the advance letter and being contacted by an interviewer may reduce the target person’s willingness to cooperate (ESS, 2012), e.g. due to forgetting the receipt of the letter (Link & Mokdad, 2005). As can be seen in Figure 6, different strategies were also observed for getting all trained interviewers to become active in the field. Of all “early starter” countries Portugal took the longest to bring on at least 50 interviewers and even this number is only the peak. The Czech Republic, on the other hand, had their full interviewer staff active from the start of fieldwork and consistently throughout it. Naturally, the rate of active interviewers goes down at the end of fieldwork, exemplified by the trajectory of Spain in the graph below (for clarity, only a selected number of countries are shown here).

Figure 6. Rate of active interviewers for “early starter” countries

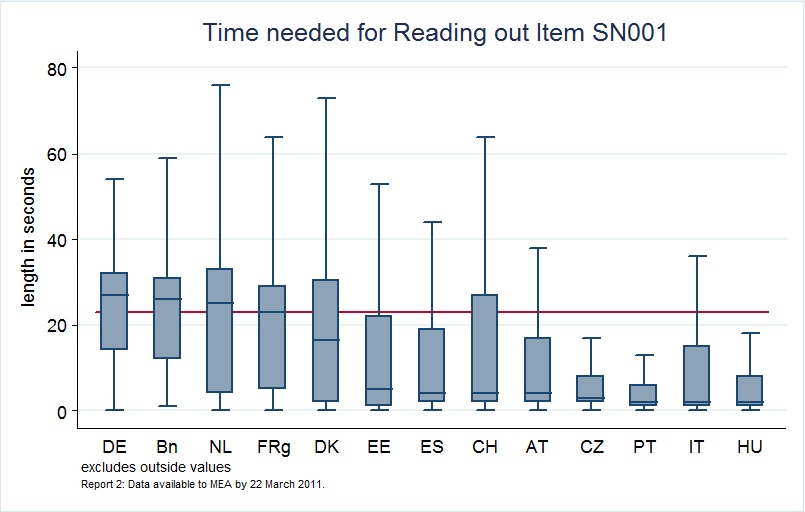

4.7 Reading times of introduction texts

Proper reading of the entire question texts (including introductions) is a key requirement of standardized interviewing (Fowler, 1991; Fowler & Mangione, 1990; Houtkoop-Steenstra, 2000) and indispensable to minimize measurement error. The “resolution” of our keystroke records allowed for separating time spent with introduction text from the time the interviewer took to read the actual question and the time it took the respondent to respond (the actual response latency). We computed the time to read out several fairly long introduction texts to identify possible deviations from a normative standard: the time to read out the English generic introduction text at proper reading speed. The introduction text was worded as follows:

“Now I am going to ask some questions about your relationships with other people. Most people discuss with others the good or bad things that happen to them, problems they are having, or important concerns they may have. Looking back over the last 12 months, who are the people with whom you most often discussed important things? These people may include your family members, friends, neighbors, or other acquaintances. Please refer to these people by their first names.”

As can be seen in Figure 7, we found strong country differences in reading out long introduction texts. Also within countries, there was large variability between interviews. The red line indicates how long it took to properly read out the English text of SN001, about 25 seconds.

Figure 7. Boxplots of read-out times for the introduction text to the Social Networks (SN) module

In our report to survey agencies, we highlighted that more than half of all countries have very high positive skew, meaning that the bulk of interviewers took very little time to read the intro to the social networks module (variable SN001). According to the keystrokes, most interviewers spent just a few seconds with the introduction text. Language differences alone cannot explain these stark differences and right-skewed distributions, especially the very short time spans of mere seconds. Clearly, interviewers cut the intro text short or skipped it entirely. Very similar findings emerged for three other “long” question texts that we checked. Again, we requested all survey agencies to relay these findings to their interviewers and to encourage them to read intro texts properly.

5. Conclusion/Discussion

The purpose of fieldwork monitoring in SHARE’s fourth wave was minimizing selected aspects of the total survey error during ongoing fieldwork by regular reporting on those indicators of data quality and stipulating corrective action.

From a technology point of view, the applicability of our procedures obviously necessitates the availability of a comparable IT system (i.e. CAPI interview software, a full electronic contact protocol and advanced internet technology). Even with a complex IT system there was still a lead time of about one week: by the time a report was sent out fieldwork had already progressed about another week. In some cases, this led to inconsistencies between fieldwork information of agencies and our reports. Also, timeliness of the data was not only dependent on a well-functioning IT system at the survey agency, but also on cooperative interviewers with internet-capable laptops. Technical issues had to be solved on a constant basis. At least one survey agency did not allow internet on their interviewers’ laptop. This created serious problems in data transmission and led to an ongoing uncertainty of the actual state of fieldwork in that country.

From a quality management point of view, SHARE followed what Lynn (2003) described as “constrained target quality approach”, where high standards were set for each country to aspire to, but reaching specified minimum quality targets was accepted (and allows for some between-country variability). We followed Lynn’s (2003) recommendations by providing constant monitoring and eventual publication of a country’s performance against ex-ante specified standards.

At the time of writing (March 2013), we are planning to conduct fieldwork monitoring with the identical conceptual approach but with improvements on the technological side, mostly related to a quicker data extraction and therefore faster turn-around of reports.

One of the key challenges in giving feedback about the status of fieldwork and suggesting corrective actions was the principal-agent problem inherent in the governance structure of SHARE. The central coordination team had no direct interaction with the actual interviewers, and was in effect quite far removed from them. In other words, all feedback to the interviewers was mediated by the management of the survey agencies or, in some cases, by the staff of scientific university teams. For good governance, we decided not to break with this arrangement by not producing interviewer-level results.

One important result will demonstrate how our monitoring efforts became an effective tool of fieldwork management that ultimately led to an improvement of data quality. In wave 4, we collected information of social networks of respondents with a new module. With the so-called “name generator approach”, respondents were asked to name as many as 7 significant others with which they communicated about important things in their lives. The CAPI instrument was programmed so that duplicates could be deleted at the end of the module to avoid measurement error (i.e. double-counting of just one network member). Early on during fieldwork, our monitoring detected that some interviewers must have misunderstood the duplicate drop and instead dropped the entire network of respondents (misunderstanding the duplicate drop as a confirmation screen). While the problem wasn’t large in absolute size (roughly 1.7 percent when first detected), there was strong interviewer clustering, i.e. only very small numbers of interviewers were responsible for the vast majority of faulty drops in each country. As mistakes during the name generator had serious negative consequences throughout the interview (because information about network members was forwarded to other modules later in the interview), addressing this problem was quite important. We sent mini-reports to each survey agency outlining which interviewers (identified through an anonymous interviewer ID) had made how many erroneous duplicate drops. We asked each survey agency to make their interviewers aware of this mistake. Our intervention showed a strong effect of cutting the rate of mistakes from 1,7 percent before to 0,9 percent after our “mini-reports intervention”.

It is my firm belief (and backed by evidence as just laid out) that any standard in survey quality set on the aggregate (usually country or survey agency) level that does not “trickle down” to the interviewer will be hard to achieve on the aggregate level: quite obviously, if high response rates (and hopefully low response bias) are a goal, interviewers should be monitored and incentivized for achieving high response rates. Without integrating interviewers, demanding the accomplishment of standards in contractual documents will be a moot point.

Appendix

Legend of line graphs

References

1. AAPOR. (2011). Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 7th edition. AAPOR. URL (1 March 2013): http://www.aapor.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Standard_Definitions2&Template=/CM/ContentDisplay.cfm&ContentID=3156

2. Das, M., Martens, M., & Wijnant, A. (2011). Survey Instruments in SHARELIFE. In M. Schröder (Ed.), Retrospective Data Collection in the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe. SHARELIFE Methodology (pp. 20-27). Mannheim: MEA.

3. ESS. (2012). Field Procedures in the European Social Survey: Enhancing Response Rates (pp. 1-10): European Social Survey.

4. Fowler, F. J. (1991). Reducing Interviewer-Related Error through Interviewer Training, Supervision, and Other Means. In: P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. E., Lyberg, N. A., Mathiowetz, S. Sudman (Eds.), Measurement Errors in Surveys (pp. 259-278). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

5. Fowler, F. J., & Mangione, T. W. (1990). Standardized Survey Interviewing: Minimizing Interviewer-Related Error. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

6. Groves, R., & Lyberg, L. (2010). Total survey error: Past, present and future. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74 (5), pp. 849-879.

7. Houtkoop-Steenstra, H. (2000). Interaction and the Standardized Survey Interview: The Living Questionnaire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

8. Koch, A., Blom, A., Stoop, I. & Kappelhof, J. (2009). Data collection quality assurance in cross-national surveys: The example of the ESS. Methoden-Daten-Analysen, 3, pp. 219-247.

9. Lepkowski, J. M., & Couper, M. P. (2002). Nonresponse in the Second Wave of Longitudinal Household Surveys. In: R. M. Groves, D. A. Dillman, J. L. Eltinge, R. J. A. Little, (Eds.), Survey Nonresponse (pp. 259-272). New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

10. Link, M. W., & Mokdad, A. (2005). Advance Letters as a Means of Improving Respondent Cooperation in Random Digit Dial Studies: A Multistate Experiment. Public Opinion Quarterly, 69(4), pp. 572-587

11. Lyberg, L. & P. B. Biemer (2008). Quality assurance and quality control in surveys. In E. D. de Leeuw, J. J. Hox, and D. A. Dillman (Eds.): International Handbook of Survey Methodology (pp. 421-441). New York: Psychology Press.

12. Lynn, P. (2003). Developing quality standards for cross-national survey research: five approaches. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, Vol. 6 (4), pp. 323-336.

13. Malter, F. & A. Börsch-Supan, A. (Eds.) (2013). SHARE Wave 4: Innovations & Methodology. Munich: MEA, Max Planck Institute for Social Law and Social Policy.

14. Watson, N., & Wooden, M. (2009). Identifying Factors Affecting Longitudinal Survey Response. In P. Lynn (Ed.), Methodology of Longitudinal Surveys (pp. 157-182). Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.