The Relationship Between Measurement Error, Representation Bias, Language, and Country: A Comparative Analysis Using the European Social Survey (Rounds 5 to 7)

Repke L. & Felderer B. (2025). The Relationship Between Measurement Error, Representation Bias, Language, and Country: A Comparative Analysis Using the European Social Survey (Rounds 5 to 7). Survey Methods: Insights from the Field, Special issue ‘Advancing Comparative Research: Exploring Errors and Quality Indicators in Social Research’. Retrieved from https://surveyinsights.org/?p=20179

© the authors 2025. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

Abstract

Survey researchers recognize that total survey error consists of multiple components, broadly pertaining to error sources and biases along the measurement process on the one hand and representation on the other hand. However, the relationship between these different error sources remains less well understood. Drawing on 1,452 estimates of measurement error from large-scale MTMM experiments in the European Social Survey, covering 24 countries and 21 languages, we investigate the relationship between measurement error, representation bias, country, and language. Our findings indicate a positive association between measurement error and representation bias. Measurement error is very similar across languages within the same country but shows some more variation between countries for the same language. We conclude that the highly professional questionnaire translation process in the ESS effectively minimizes the impact of language differences on measurement error, while cultural differences and variations in sample composition continue to play a crucial role in contributing to measurement error.

Keywords

data quality, ESS, measurement error, MTMM experiments, representation bias

Copyright

© the authors 2025. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

Introduction

In a world where public opinion, often captured through surveys, informs policy-making decisions, the accuracy of the measurement instruments (i.e., survey items) used to elicit respondents’ opinions is crucial (Groves, 2005). Measurement quality is the basis of credible research (Alwin, 2007; Repke et al., 2024; Saris & Gallhofer, 2007). It determines to what extent the collected data reflect the realities of the population under study (Biemer, 2010). High-quality instruments with minimal measurement error ensure that the nuanced opinions, attitudes, and behaviours of individuals are captured well, ultimately allowing researchers and policymakers to draw meaningful conclusions. However, designing such high-quality measurement instruments is a complex task, especially in cross-national research projects that must account for many languages, cultures, and institutional settings (Boer et al., 2018; Davidov et al., 2014; Harkness et al., 2003; Saris, 1998). Even small differences in the wording of the translations, for instance, can alter the meaning of an item or change the properties of an answer scale (e.g., turning a bipolar scale into a unipolar scale), introducing additional error at the measurement level (Repke & Dorer, 2021).

Beyond measurement challenges, large cross-national surveys—such as the European Social Survey (ESS)—must also address factors that can introduce bias at the level of representation (see, e.g., Rybak, 2023). Even in surveys based on probability samples, like the ESS, not all sampled individuals respond to the survey, most commonly because they either refuse to participate or cannot be contacted (Groves & Couper, 1998; Stoop, 2005). If survey nonresponse is more prevalent among certain population groups—such as individuals with lower levels of education—these groups may be underrepresented in the survey, potentially leading to nonresponse bias (Groves & Peytcheva, 2008), a key source of representation bias. Ideally, all participating countries would utilize the same sampling frame and apply identical sampling procedures, resulting in national samples that represent their populations in a comparable way. In practice, however, national coordination teams often need to implement different sampling designs and work with different data collection agencies (Jowell et al., 2007). This reduces control over the sampling process and results in samples that vary in how well they represent each country’s population, further adding to representation bias (Menold, 2014). In the following, we use the term representation bias to refer to differences in the socio-demographic composition between the survey respondents and the target population.

Error Sources and Quality Estimation

In survey methodology, the two primary sources of error and bias—those related to measurement and those related to representation—are typically treated as two independent dimensions within the Total Survey Error (TSE) framework. This conceptual model links each step of the survey process—design, data collection, and estimation—to these two error sources (for a graphical illustration, see Groves & Lyberg, 2010; Groves et al., 2011). Measurement errors affect the accuracy of individual responses, while representation biases arise when the achieved sample of survey respondents does not adequately reflect the target population.

Although this distinction is widely accepted, these two error sources can also interact in meaningful ways, especially in cross-cultural surveys, where both measurement quality and representation can vary across countries and languages. For example, a translation’s degree of adaptiveness versus functional equivalence may influence measurement error differently depending on respondents’ cultural backgrounds (Repke & Dorer, 2021). In contrast, different sampling strategies may over- or underrepresent certain linguistic or demographic groups.

Conceptually, measurement error refers to the discrepancy between the observed responses to a survey item and the true value of the measured construct. Within the framework of classical test theory, this is expressed as the observed score being the sum of the true score and an error component (Alwin, 2007; Gulliksen, 2013; Lord & Novick, 2008; Saris & Gallhofer, 2007). This error is typically assumed to be random, resulting from factors such as respondents accidentally providing incorrect answers or interviewers making recording errors. However, measurement error can also contain a systematic component, as in the true score model proposed by Saris and Andrews (1991). This type of error—often referred to as method effect—stems from features of the survey item’s design (e.g., question wording or the format of the answer scale), which can influence how respondents interpret and answer survey questions (Saris & Gallhofer, 2007).

Researchers typically estimate the size of the average measurement error empirically, using data collected from actual survey respondents. However, these estimates are not immune to representation issues. If the sample does not adequately represent the target population, the resulting measurement quality estimates may be biased, reflecting the characteristics of the sampled respondents rather than the population under study (Biemer, 2010). For instance, if the sample disproportionally includes women or younger individuals, the estimated measurement error may reflect how these specific groups interpret and react to survey items—potentially diverging from how men or older respondents would respond. These group-specific response tendencies are often referred to as response functions (see Saris, 1988). In this way, measurement error estimates are inherently tied to the composition of the sample used for analysis.

One established method for estimating measurement quality is the multitrait-multimethod (MTMM) approach, originally proposed by Campbell and Fiske (1959) and further developed by Saris and Andrews (1991). In an MTMM design, several related constructs (known as traits) are repeatedly measured using different methods—commonly different response scales or question formats. The goal is to disentangle the variance in survey responses attributable to the construct of interest from the variance introduced by the measurement method.

The typical MTMM experiment uses a 3×3 design in which three traits are each measured with three different methods. This setup allows researchers to estimate reliability (the consistency of the measure) and validity (the degree to which the measure reflects the intended construct) of each measurement and to isolate systematic method effects. To analyze MTMM data, researchers can use different statistical models. The classical MTMM model applies confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to account for trait and method variance in the observed correlations (e.g., Jöreskog, 1970; Althauser et al., 1971; Alwin, 1973). An alternative is the true score model, which decomposes measurement quality into reliability and validity and allows for the estimation of the method effect (for detailed information, see Saris and Andrews, 1991; Saris et al., 2022).

Although measurement error may consist of multiple components (see, e.g., Backström et al., 2025), this paper focuses on the systematic component of measurement error (i.e., the method effect), which we define as:

measurement error = 1 – validity

While the discussed models provide valuable estimates of measurement quality, their assumptions do not always hold in practice. A notable example is the assumption of independent repeated measurements in MTMM designs. Schwarz et al. (2020) demonstrate that memory effects—respondents recalling their previous answers and replicating them—can violate this assumption, leading to biased estimates of measurement quality. This underscores the need for caution when interpreting MTMM-based estimates.

Comparability in Practice: The ESS

The ESS is a biennial, large-scale cross-national survey that collects data on social attitudes, political opinions, preferences, and behaviours across many European countries. Established in 2001, the ESS employs random probability sampling to generate representative samples of individuals aged 15 and above residing in private households in participating countries. To date, 39 countries have taken part in at least one ESS round (European Social Survey, 2024; see also www.europeansocialsurvey.org).

Widely regarded for its rigorous methodological standards, the ESS has been recognized as a benchmark for high-quality cross-national survey research (Jowell et al., 2007; Stoop et al., 2010). As part of its commitment to data quality, the ESS systemically evaluates measurement error using MTMM experiments based on the true score model by Saris and Andrews (1991; for an example, see Poses et al., 2021). So far, MTMM experiments have been conducted in ESS rounds 1 to 9, covering variables such as political efficacy, media use, social trust, and attitudes toward immigration.

These experiments have also laid the foundation for the Survey Quality Predictor (SQP), an open-access software designed to predict the quality of survey items. The tool is based on a meta-analysis of the formal and linguistic characteristics of thousands of survey questions and their quality estimates, primarily obtained from MTMM experiments conducted within the ESS (Saris et al., 2000; Saris, 2001; Saris et al., 2004, 2011; Felderer et al., 2024). It is available online at sqp.gesis.org. Not only was SQP developed within the ESS context, but it has also been applied actively in the survey’s operational processes, including the development of the source questionnaire and during translation checks (see, e.g., European Social Survey, 2018).

Additionally, the ESS monitors the socio-demographic composition of its samples to ensure that they adequately reflect the target population. In rounds 5 to 7, sample compositions (e.g., gender, age, work status, and nationality) were compared with external benchmark data from the European Labour Force Survey (EU-LFS; see https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/microdata/european-union-labour-force-survey). Note that, because these data are available only at the country level, they cannot be used to assess the socio-demographic representation of linguistic subgroups within countries.

The Current Study

This paper investigates the interplay between measurement error, representation bias, language, and country in the ESS. By exploring how measurement errors in survey items vary across different European countries and linguistic groups, this study seeks to uncover factors influencing data quality in comparative social research. It addresses two key research questions (RQ):

- To what extent are the measurement errors of survey items associated with representation bias?

- Do measurement errors of survey items vary across different country-language groups? And if yes, how?

Data and Method

MTMM Experiments in the ESS

We use data from ESS rounds 5 to 7, encompassing 1,452 measurement estimates for 93 items fielded across 24 countries and 21 languages. These rounds were selected because they are the only ones for which both measurement quality estimates from MTMM experiments and detailed sample composition information are available in a consistent and comparable format. Earlier rounds were excluded due to missing sample composition data. Round 8 was not included because the MTMM estimates were based on a different analytical procedure, which renders its results not directly comparable to those from rounds 5 to 7. Although round 9 returned to the original analytical approach, it was excluded to preserve a continuous and methodologically consistent time series.

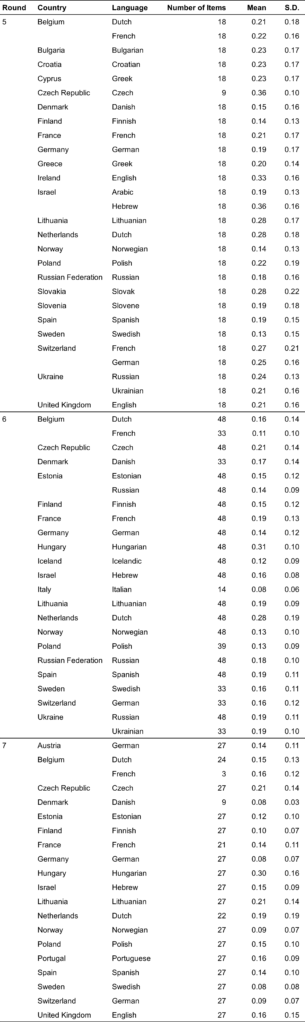

Table 1 presents the number of items, along with the mean and standard deviation of measurement error for all items within each country-language group, broken down by ESS round. The observed variation in mean measurement error across these groups indicates that, on average, the questionnaire performs better in some country-language contexts than in others. For instance, in round 5, the Swedish items in Sweden show the lowest mean measurement error, whereas the Hebrew items in Israel exhibit the highest. Notably, the Arabic items in Israel display considerably lower measurement error, highlighting the potential influence of language context within the same country. Examining the distribution of measurement errors within country-language groups reveals that the Slovakian items in Slovakia, in round 5, have the highest standard deviation. This suggests greater variability in measurement error across items compared to other country-language groups, indicating that some items perform much better—or worse—than others within that context.

Table 1

Mean Measurement Error and Standard Deviation Over All Items by Country-Language Group and ESS Round

Note. In rounds 6 and 7, some items were not fielded in certain country-language groups.

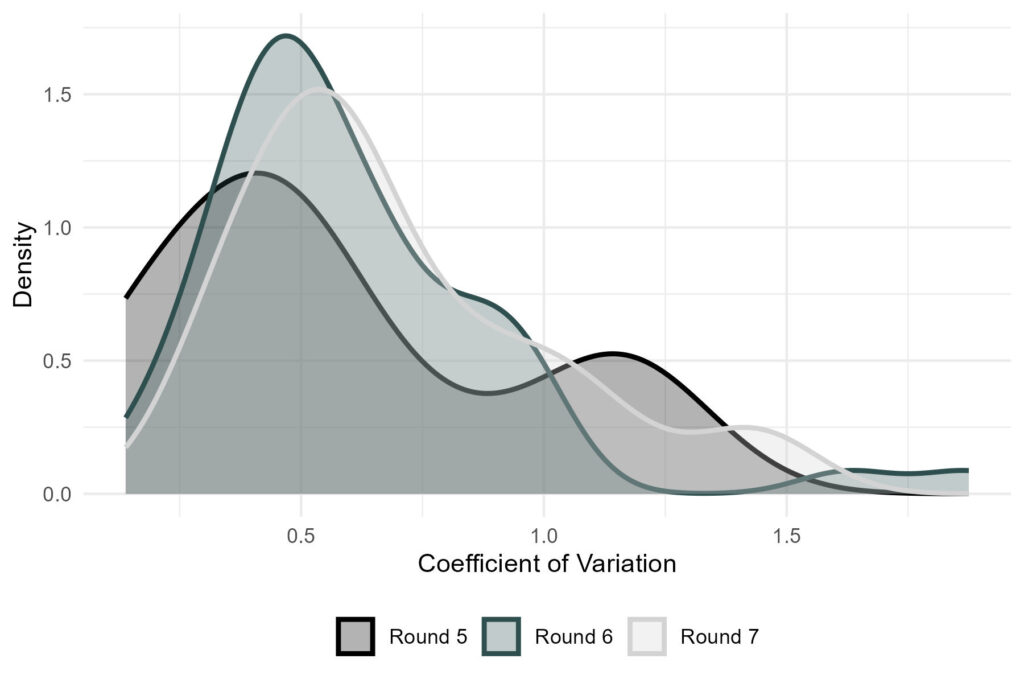

An examination of the distribution of measurement error—characterized by mean and standard deviation for each item across the different country-language groups—reveals substantial variation between groups (see Table A1 in the Appendix). This suggests that the same item may exhibit low measurement error in one group but high error in another. To quantify this variability in a standardized way across the different items, we computed the coefficient of variation (CV) for each item, defined as the ratio of the standard deviation to the mean measurement error across the country-language groups:

CV =

standard deviation mean

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of CVs for all items in each of the three ESS rounds. The results show that the CVs are centered around 0.5 in all rounds but show considerable spread. A low CV indicates that measurement error is relatively consistent across country-language groups for a given item, whereas a high CV signals pronounced differences in measurement error between country-language groups. For reference, a CV of 0.5 implies that the standard deviation is half the size of the mean measurement error.

Figure 1. Distributions of the Coefficients of Variation of Measurement Error Across Country-Language Groups for All Items in ESS Rounds 5 to 7

Representation Bias in the ESS Compared to Benchmarks from the EU-LFS

The EU-LFS is an annual, large-scale probability-based survey of residents in private households across Europe, covering many of the same countries as the ESS. Following the argumentation of Koch et al. (2014) and Koch (2016, 2018), we consider the EU-LFS a useful data set for evaluating representation bias in the ESS. Building on their approach, our analysis relies on the dissimilarity scores reported by these authors to compare ESS samples to corresponding EU-LFS data.

Specifically, Koch and colleagues use Duncan’s index of dissimilarity (Duncan & Duncan, 1955) to assess representation bias for the variables gender, age, marital status, work status, nationality, and household size—provided these characteristics are available from the EU-LFS. The index ranges from 0 to 100, where 0 indicates identical distributions (i.e., no differences) between the ESS and the EU-LFS, and 100 represents complete dissimilarity. Duncan’s dissimilarity index reflects the percentage of respondents that would need to change categories in the ESS to achieve perfect alignment with the EU-LFS distribution (Koch et al., 2014).

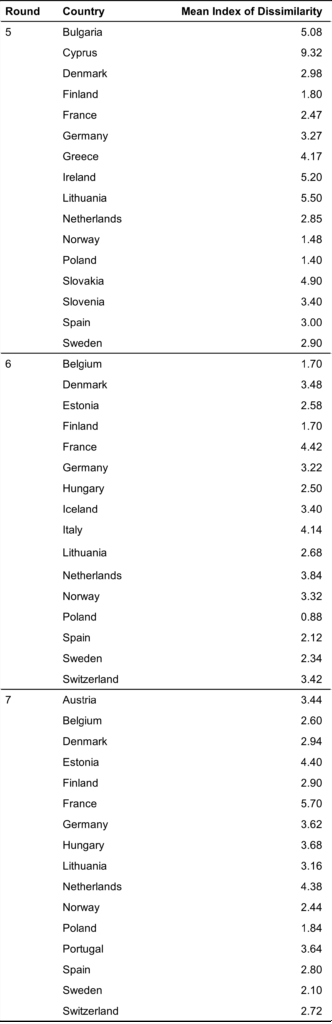

Due to missing EU-LFS data in some countries, household size is excluded from our analysis for all rounds, and marital status is excluded for round 5. For all available variables, we calculate the average of the reported dissimilarity indices across all socio-demographic characteristics for each country, producing a country-level aggregate measure of representation bias (see Table 2).

Table 2

Mean Index of Dissimilarity

Note. The table is generated based on the information presented in Koch et al. (2014) and Koch (2016, 2018). The index averages the dissimilarity indices of gender, age, work status, nationality, and marital status, the latter only being available for rounds 6 and 7.

Our analysis of representation bias is restricted to the country level, as the EU-LFS does not allow for differentiation by language groups within countries. As a result, we cannot assess how well specific language populations (e.g., German-speaking Swiss respondents) are represented relative to their respective subpopulations. Further, given that measurement error estimates from the MTMM experiments are available at the country-language level, we cannot assess representation bias in countries with more than one common language. Consequently, this limitation precludes us from including multilingual countries in the representation bias analysis.

To study the relationship between measurement error and representation bias, we regressed measurement error on the average dissimilarity index per country. The analysis combines data from rounds 5 to 7 and uses multilevel models to account for the hierarchical structure of the data, including random intercepts for items and countries. We ran beta regression to allow the measurement error to only take values between 0 and 1, using the package glmmTMB (Brooks et al., 2017) in R.

Results

This section presents our findings, structured according to the two guiding research questions.

RQ1. Association Between Measurement Error and Representation Bias

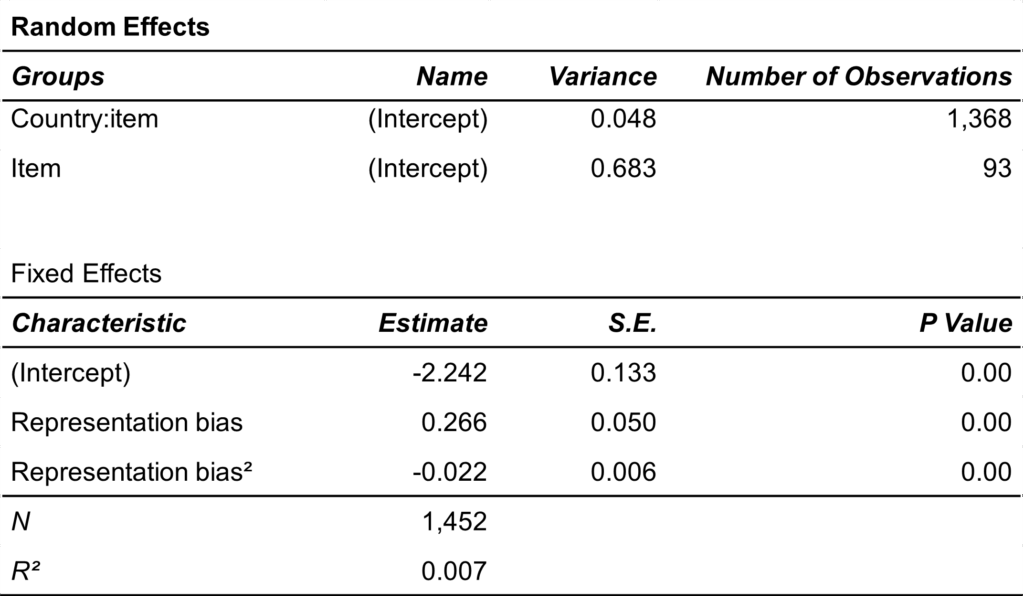

To address our first research question—examining the extent to which measurement errors are associated with representation bias—we performed a multilevel beta regression analysis. Measurement error was regressed on representation bias, as measured by Duncan’s dissimilarity index. To account for potential non-linear effects, we included both a linear and a squared term for representation bias in the model. The model incorporates random intercepts to account for the nested structure of the data. Table 3 summarizes the results for the random effects and fixed effects.

Table 3

Multi-Level Beta Regression Results: Measurement Error as a Function of Representation Bias Measured Using Duncan’s Dissimilarity Index

First, the estimated variance components of the random intercepts show that most of the unexplained variation of measurement error can be attributed to the item level rather than the country:item level. Second, the fixed effects of both the linear and squared terms of representation bias are statistically significant, suggesting a curvilinear relationship between representation bias and measurement error. However, including only representation bias as an independent variable explains little variation in measurement error (R² = 0.007).

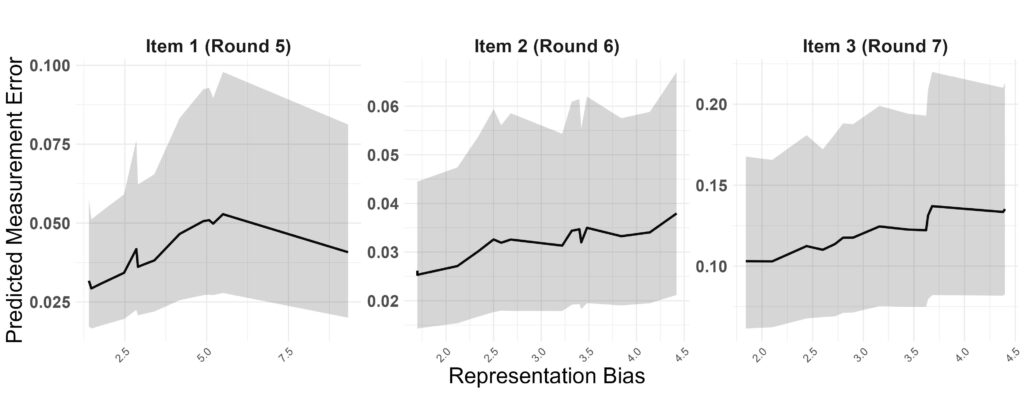

To illustrate the relationship between measurement error and representation bias, we present the predicted measurement errors for three example items, one for each ESS round under study:

- Item 1 (ESS round 5)

BYSTLCT – Risk of sanction, bought stolen goods

“Using this card, please tell me how likely it is that you would be caught and punished if you…

… bought something you thought might be stolen?”

Response format: second statement of an item battery rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all likely) to 4 (very likely)

- Item 2 (ESS round 6)

ImWBCnt – Immigration consequences, country worse or better

“Is [country] made a worse or a better place to live by people coming to live here from other countries? Please use this card.”

Response format: 11-point scale ranging from 0 (worse place to live) to 10 (better place to live)

- Item 3 (ESS round 7)

ACTROLG – Able to take active role in political group

“How able do you think you are to take an active role in a group involved with political issues? Please use this card.”

Response format: 11-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all able) to 10 (completely able)

Figure 2 visualizes the predicted measurement errors along with their 95% confidence bands for these three items. For item 1, the relationship follows a curvilinear pattern. Measurement error increases with representation bias up to a value of around 5, and then decreases at higher levels of representation bias. Representation bias in rounds 6 and 7 does not exceed a value of 5, thus, no reversal effect is observed for items 2 and 3, which were fielded in those rounds.

Figure 2. Illustration of Regression Model (Table 3) With Three Items Selected as Examples, One for Each Round of the ESS

Note. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence bands.

RQ2. Differences in Measurement Error Between Different Country-Language Groups

To address our second research question—examining whether and how measurement error varies across different country-language groups—we conducted two complementary analyses. First, we compared measurement error for different languages within the same country at the item level. Second, we compared measurement errors across different countries that conducted interviews in the same language.

Measurement Error Differences Between Different Languages Within the Same Country

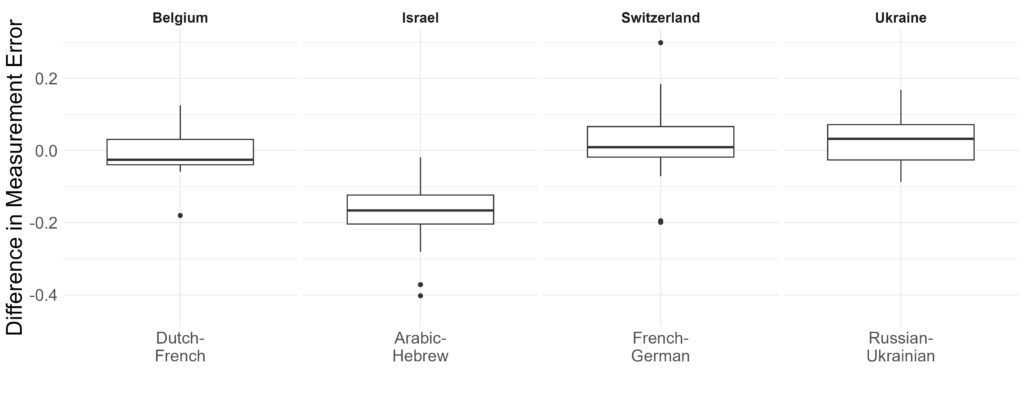

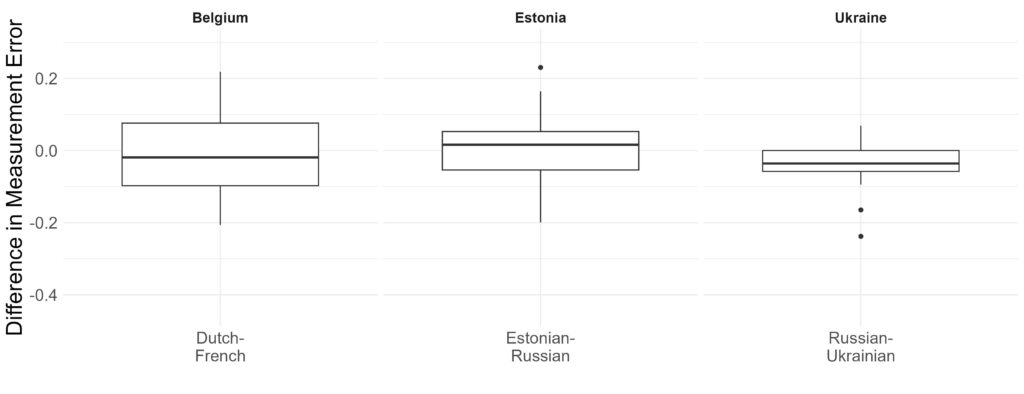

This analysis is restricted to countries where the ESS administered MTMM experiments in their questionnaires in multiple languages. For round 5, these countries were Belgium, Israel, Switzerland, and Ukraine; for round 6, Belgium, Estonia, and Ukraine; and for round 7, only Belgium. Due to the small number of items included in the French questionnaire version in round 7 (3 items vs. 24 in the Dutch version), we excluded Belgium from this analysis.

We computed the differences in measurement error per item, including only items that appeared in all language versions of the questionnaire within each country. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate the distributions of these differences between languages for the countries of rounds 5 and 6, respectively. In round 5 (Figure 3), average differences in measurement error were close to zero for Belgium and Switzerland, although some variation exists. Specifically, on average, Dutch items in Belgium showed slightly lower measurement error than French items, while French items in Switzerland showed slightly higher measurement error than German items. In Ukraine, Russian items generally exhibited higher measurement error than Ukrainian items, though some items reversed this pattern. In Israel, Arabic items consistently showed lower measurement error compared to Hebrew items.

In round 6 (Figure 4), similar patterns emerged. Belgium again showed near-zero average differences, with French items having slightly higher measurement error than Dutch items. In Estonia, differences were minimal, with Estonian items outperforming Russian items. Ukraine showed a reversed pattern compared to round 5: Ukrainian items had higher measurement error on average than Russian items.

Measurement Error Differences for the Same Language Across Countries

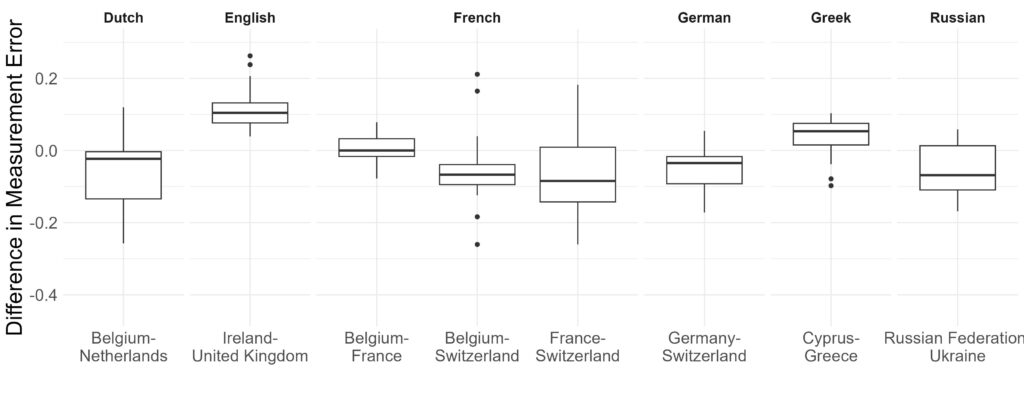

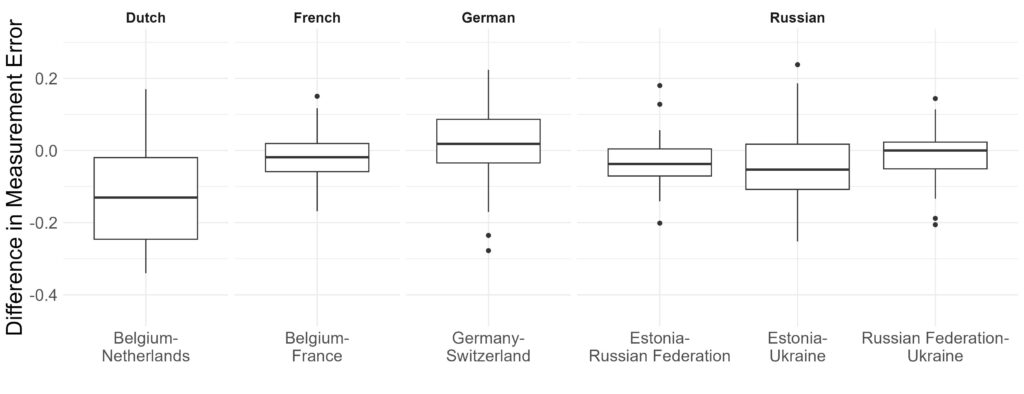

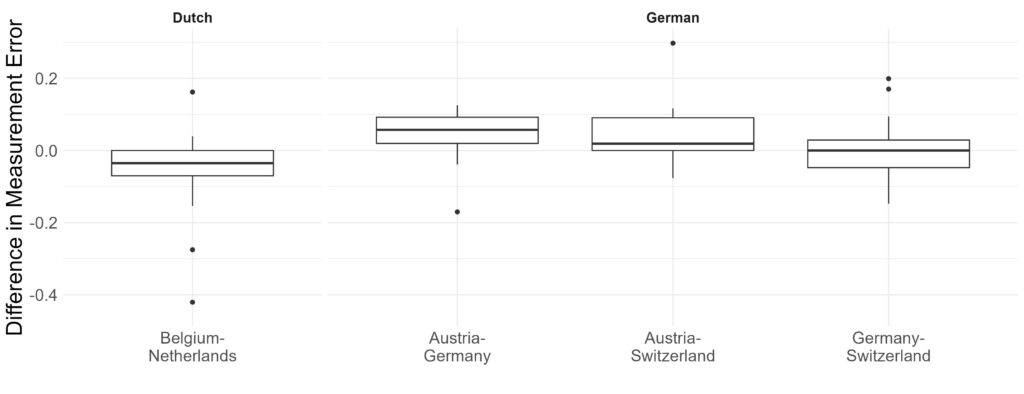

To examine the differences in measurement error for the same language across countries, we included only languages fielded in multiple countries within the ESS. In round 5, these languages were Dutch, English, French, German, Greek, and Russian; in round 6, Dutch, French, German, and Russian; and in round 7, Dutch and German.

Figure 5 displays the differences in measurement error for round 5. Dutch items performed better (i.e., exhibited lower measurement error) in Belgium than in the Netherlands. English items showed consistently higher measurement error in Ireland compared to the United Kingdom.

For French, items were fielded in Belgium, France, and Switzerland. Thus, Figure 5 holds three boxplots for each possible country-pair comparison. The average measurement error difference between Belgium and France was zero, with very low variation. Belgium, however, showed lower measurement error than Switzerland for most items. The largest and most variable differences were between France and Switzerland, with Switzerland exhibiting much higher measurement error on average, although item-level variation suggests some items perform better in France and others in Switzerland.

German items had higher measurement error in Switzerland compared to Germany. For Greek, items fielded in Cyprus showed higher measurement error than those in Greece, with only a few exceptions. Finally, Russian items in Ukraine had markedly higher measurement error than those in the Russian Federation.

Figure 6 presents the finding of round 6, largely mirroring round 5. Dutch again had lower measurement error in Belgium than in the Netherlands. French items showed small differences, with slightly higher error in France than Belgium. German items exhibited slightly higher measurement error in Germany relative to Switzerland. Russian items, fielded in the Russian Federation, Ukraine, and Estonia, showed the largest differences between Estonia and Ukraine, with higher error in Ukraine. Estonia also had higher measurement error than the Russian Federation, while differences between the Russian Federation and Ukraine were minimal (i.e., median difference of around zero).

The analysis of ESS round 7 (see Figure 7) replicates the above-mentioned pattern of Dutch items exhibiting higher measurement error in the Netherlands compared to Belgium. German items, fielded in Austria, Switzerland, and Germany, had consistently higher measurement error in Austria relative to the other two countries. Differences between Switzerland and Austria were smaller but with more variation, while the median difference between Germany and Switzerland was close to zero.

Discussion

This paper explored the interplay between measurement error, representation bias, language, and country using items from rounds 5 to 7 of the ESS, as well as quality estimates from various MTMM experiments. In addressing our first research question—examining the extent to which measurement error is associated with representation bias—we find a positive relationship between measurement error and representation bias across all items and countries in the three ESS rounds. Notably, this relationship is found to be non-linear, with a reversal observed at very high levels of representation bias. However, since such high biases are only present in round 5, this reversal effect should be interpreted cautiously. Overall, the findings reinforce the ideas that higher representation bias is associated with greater measurement error, underscoring the importance of addressing both error sources in survey design and evaluation.

Regarding our second research question—analyzing the variation in measurement error between country-language groups—we find that measurement error is generally very similar across different language versions of the questionnaire within the same country. The notable exception is Israel in round 5, where Hebrew items consistently showed higher measurement error than Arabic ones. This could potentially reflect differences in translation quality or how different cultural or linguistic groups interpret survey items. Moreover, this case could exemplify how varying representation bias across language groups might contribute to differences in measurement error.

When comparing the same language across different countries, we consistently find that Dutch items showed higher measurement error in the Netherlands than in Belgium. However, results for other languages are more mixed. German produced less measurement error in Germany than in Switzerland in round 5, but very little differences were observed in rounds 6 and 7. French items generally showed low differences in measurement error between France and Belgium, but large differences between France and Switzerland, as well as between Belgium and Switzerland—particularly in round 6. Notably, the variation in measurement error differences for French items was much higher between France and Switzerland than in other country comparisons. These findings suggest that measurement error differences across countries are item-specific and context-dependent, warranting further investigation to assess their consistency over time.

The results for Russian were similarly mixed. In round 5, measurement error was higher in Ukraine than in the Russian Federation. In round 6, however, average differences were close to zero, with much lower variability. Also, Estonia exhibited lower measurement error than both Ukraine and the Russian Federation, though the differences and variations were greater between Estonia and Ukraine. As these comparisons are limited to a single round, further studies are needed to evaluate the consistency of these findings across other rounds. Moreover, measurement error differences between England and Ireland were minimal, with little variability, whereas Greek items showed higher measurement error in Cyprus than in Greece.

Our findings support the argument that measurement error and representation bias are not independent phenomena. Rather, they are interrelated aspects of survey quality and should be considered jointly, especially in cross-national survey research. Efforts taken to optimize one error source can potentially reduce other sources of error as well, directly and indirectly improving overall data quality. The ESS, with its rigorous translation procedures and quality control protocols, offers an ideal case for studying the relationship between measurement error, representation bias, language, and country.

However, some limitations must be acknowledged. First, our analysis focused exclusively on attitudinal questions, as factual questions are not included in the MTMM design. Future research should investigate factual questions using external benchmarks. Second, we were unable to isolate the individual contributions of country, language, sample composition, and culture to measurement error. Assuming that groups within the same country share a common cultural background, we expect differences between languages within a country to be driven more by language than culture, whereas differences in the same language between countries may be more influenced by cultural and institutional factors.

That said, the generally low differences in measurement error between language groups within the same country suggest a high standard of translation quality within the ESS. However, further research is needed to better understand cross-country differences for the same language. Future studies should examine the representation of language subgroups, as one hypothesis would be that smaller language groups or languages not dominant in a country (e.g., French in Switzerland) may be underrepresented in the ESS, leading to higher measurement error. Another hypothesis might be that cultural differences between language groups cause differences in measurement error.

In summary, our study highlights the complex interplay between measurement error, representation bias, language, and culture in cross-national surveys like the ESS. Although high-quality translation practices may help minimize language-related differences in measurement error, cultural and representation-related factors could still significantly contribute to measurement error variability across countries. Keeping this in mind and addressing these error sources will be crucial for improving data quality in cross-national surveys. If possible, future research should aim to disentangle these factors more precisely by investigating how survey design, translation strategies, and cultural context jointly shape measurement error across diverse cultural and linguistic settings. Such efforts are critical for enhancing the quality and comparability of data in cross-national research.

Appendix

References

- Althauser, R. P., Heberlein, T. A., & Scott, R. A. (1971). A Causal Assessment of Validity: The Augmented Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix.Causal Models in the Social Sciences, 374–399.

- Alwin, D. F. (1973). Approaches to the Interpretation of Relationships in the Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix. Sociological Methodology 5, 79–105.

- Alwin, D. F. (2007). Margins of Error: A Study of Reliability in Survey Measurement. Wiley.

- Backström, K., Cernat, A., Sirén, R., & Söderlund, P. (2025). Measurement error when surveying issue positions: a MultiTrait MultiError approach. Political Science Research and Methods, 1–18. doi: 10.1017/psrm.2025.31

- Biemer, P. P. (2010). Total Survey Error: Design, Implementation, and Evaluation. Public Opinion Quarterly, 74(5), 817–848. doi: 10.1093/poq/nfq058

- Boer, D., Hanke, K., & He, J. (2018). On Detecting Systematic Measurement Error in Cross-Cultural Research: A Review and Critical Reflection on Equivalence and Invariance Tests. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(5), 713–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022117749042

- Brooks, M. E., Kristensen, K., van Benthem, K. J., Magnusson, A., Berg, C.W., Nielsen, A., Skaug, H. J., Maechler, M. & Bolker, B. M. (2017). GlmmTMB Balances Speed and Flexibility Among Packages for Zero-Inflated Generalized Linear Mixed Modeling. The R Journal 9 (2), 378–400.

- Campbell, D. T. & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and Discriminant Validation by the Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix. Psychological Bulletin 56 (2), 81–105.

- Davidov, E., Meuleman, B., Cieciuch, J., Schmidt, P., & Billiet, J. (2014). Measurement equivalence in cross-national research. Annual Review of Sociology, 40(1), 55-75.

- Duncan, O. D. & Duncan, B. (1955). A Methodological Analysis of Segregation Indexes. American Sociological Review 20 (2), 210–217.

- European Social Survey (2018). Round 9 Survey Specification for ESS ERIC Member, Observer and Guest Countries. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/sites/default/files/2023-06/ESS9_project_specification.pdf#:~:text=The%20present%20document,%20called%20the%20Specifications%20for%20short,l.

- European Social Survey (2024). Prospectus. European Social Survey. European Research Infrastructure Consortium. Revised and Updated. https://www.europeansocialsurvey.org/sites/default/files/2024-04/prospectus_updated.pdf

- Felderer, B., Repke, L., Weber, W., Schweisthal, J., & Bothmann, L. [Forthcoming]. Predicting the Validity and Reliability of Survey Questions: An Update of the Prediction Algorithm in the Survey Quality Predictor. Survey Research Methods.

- Groves, R. M. (2005). Survey errors and survey costs. John Wiley & Sons.

- Groves, R. M., & Couper, M. P. (1998). Nonresponse in Household Interview Surveys. Wiley.

- Groves, R. M., Fowler Jr, F. J., Couper, M. P., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., & Tourangeau, R. (2011). Survey Methodology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Groves, R. M., & Lyberg, L. (2010). Total Survey Error: Past, Present, and Future. Public Opinion Quarterly 74 (5), 849–879.

- Groves, R. M., & Peytcheva, E. (2008). The Impact of Nonresponse Rates on Nonresponse Bias: A Meta-Analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(2), 167-189.

- Gulliksen, H. (2013). Theory of Mental Tests. Routledge.

- Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R., & Eva, G. (2007). Measuring attitudes cross-nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey. Sage.

- Harkness, J. A., Van de Vijver, F. J., & Mohler, P. P. (2003). Cross-Cultural Survey Methods. Wiley.

- Heise, D. R. (1969). Separating reliability and stability in test-retest correlation. American Sociological Review, 34(1), 93–101. doi: 10.2307/2092790

- Jöreskog, K. G. (1970). A General Method for Estimating a Linear Structural Equation System. ETS Research Bulletin Series 1970 (2), i–41.

- Jowell, R., Roberts, C., Fitzgerald, R., & Eva, G. (Eds.). (2007). Measuring attitudes cross-nationally: Lessons from the European Social Survey. Sage.

- Koch, A. (2016). Assessment of Socio-Demographic Sample Composition in Ess Round 6. Technical report, European Social Survey, GESIS, Mannheim.

- Koch, A. (2018). Assessment of Socio-Demographic Sample Composition in Ess Round 7. Technical report, European Social Survey, GESIS, Mannheim.

- Koch, A., Halbherr, V., Stoop, I. A., & Kappelhof, J. W. (2014). Assessing Ess Sample Quality by Using External and Internal Criteria. Mannheim: European Social Survey, GESIS.

- Lord, F. M., & Novick, M. R. (2008). Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores. IAP.

- Menold, N. (2014). The influence of sampling method and interviewers on sample realization in the European Social Survey. Survey Methodology, 40(1), 105-123.

- Poses, C., Revilla, M., Asensio, M., Schwarz, H., & Weber, W. (2021). Measurement Quality of 67 Common Social Sciences Questions Across Countries and Languages Based on 28 Multitrait-Multimethod Experiments Implemented in the European Social Survey. Survey Research Methods, 15(3), 235–256. doi: 10.18148/srm/2021.v15i3.7816.

- Repke, L., Birkenmaier, L., & Lechner, C. (2024). Validity in Survey Research-From Research Design to Measurement Instruments. GESIS Survey Guides. doi: 10.15465/gesis-sg_en_048

- Repke, L., & Dorer, B. (2021). Translate Wisely! An Evaluation of Close and Adaptive Translation Procedures in an Experiment Involving Questionnaire Translation. International Journal of Sociology, 51(2), 135–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207659.2020.1856541

- Rybak, A. (2023). Survey mode and nonresponse bias: A meta-analysis based on the data from the international social survey programme waves 1996–2018 and the European social survey rounds 1 to 9. Plos one, 18(3), e0283092.

- Saris, W. E. (1988). Variation in Response Functions: A Source of Measurement Error in Attitude Research. Amsterdam: Sociometric Research Foundation.

- Saris, W. E. (1998). The effects of measurement error in cross-cultural research. In J. Harkness (Ed.), Cross-cultural survey equivalence (pp. 67–84). Zentrum für Umfragen, Methoden und Analysen (ZUMA).

- Saris, W. E. (2001). SQP: Survey Quality Predictor. DOS Application Program.

- Saris, W. E. & Andrews, F. M. (1991). Evaluation of Measurement Instruments Using a Structural Modeling Approach. In P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. E. Lyberg, N. A. Mathiowetz, and S. Sudman (Eds.), Measurement Errors in Surveys, pp. 575–597. Wiley.

- Saris, W. E., & Gallhofer, I. N. (2007). Design, evaluation, and analysis of questionnaires for survey research. In Wiley Series in Survey Methodology. John Wiley & Sons.

- Saris, W. E., Oberski, D., & Kuiper, S. (2004). SQP: Survey Quality Predictor. DOS application program.

- Saris, W. E., Oberski, D., & Weber, W. (2022). The Quality of Survey Questions for Continuous Latent Variables: Your Guide to the Sqp Database and Predictions (1st ed.). Independently published.

- Saris, W. E., Oberski, D. L., Revilla, M., Zavala-Rojas, D., Lilleoja, L., Gallhofer, I., & Gruner, T. (2011). The Development of the Program Sqp 2.0 for the Prediction of the Quality of Survey Questions. Working Paper Number 24 of the Series of the Research and Expertise Centre for Survey Methodology (RECSM).

- Saris, W. E., van der Veld, W., & Gallhofer, I. (2000). A Program for Prediction of the Quality of Survey Measurement. Paper presented in October 2020 at the Methodology Conference in Köln, Germany.

- Schwarz, H., Revilla, M., & Weber, W. (2020). Memory Effects in Repeated Survey Questions: Reviving the Empirical Investigation of the Independent Measurements Assumption. Survey Research Methods, 14(3), 325–344. doi: 10.18148/srm/2020.v14i3.7579

- Stoop, I. A. L. (2005). The Hunt for the Last Respondent: Nonresponse in Sample Surveys. SCP, Social and Cultural Planning Office of the Netherlands.

- Stoop, I. A., Billiet, J., Koch, A., & Fitzgerald, R. (2010). Improving survey response: Lessons learned from the European Social Survey. John Wiley & Sons.

- Wiley, D. E., & Wiley, J. A. (1970). The estimation of measurement error in panel data. American Sociological Review, 35(1), 112–117. doi: 10.2307/2093858