A Case Study of Error in Survey Reports of Move Month Using the U.S. Postal Service Change of Address Records

Mulry, Mary H., Nichols, Elizabeth M. & Childs, Jennifer Hunter. (2016). A Case Study of Error in Survey Reports of Move Month Using the U.S. Postal Service Change of Address Records, Survey Methods: Insights from the Field. Retrieved from https://surveyinsights.org/?p=7794

© the authors,

Abstract

Correctly recalling where someone lived as of a particular date is critical to the accuracy of the once-a-decade U.S. decennial census. The data collection period for the 2010 Census occurred over the course of a few months: February to August, with some evaluation operations occurring up to 7 months after that. The assumption was that respondents could accurately remember moves and move dates on and around April 1st up to 11 months afterwards. We show how statistical analyses can be used to investigate the validity of this assumption by comparing self-reports and proxy-reports of the month of a move in a U.S. Census Bureau survey with an administrative records database from the U.S. Postal Service containing requests to forward mail filed in March and April of 2010. In our dataset, we observed that the length of time since the move affects memory error in reports of a move and the month of a move. Also affecting memory error of moves is whether the respondent is reporting for themselves or another person in the household . This case study is relevant to surveys as well as censuses because move dates and places of residence often serve as anchors to aid memory of other events in questionnaires.

Keywords

administrative records, measurement error, recall error, telescoping

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Eric Slud, Lin Wang, and Magdalena Ramos for their helpful comments on this manuscript. This article is released to inform interested parties and encourage discussion of work in progress. The views expressed on statistical, methodological, and operational issues are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the U.S. Census Bureau.

This paper is a rework of previous submission.

Copyright

© the authors,

1. Introduction

In the 2010 Census, all persons living in the U.S. were counted at the place they were living as of Census Day, April 1, 2010. The data collection for that census took place over the course of a few months: February to August, with some evaluation operations occurring up to 11 months after Census Day. Respondents reported information for their households by mail or by speaking with an interviewer over the telephone or in person. For data collections occurring after Census Day, respondents often had to rely on their memory to determine where they were living on April 1. In part, the success of the census depended upon respondents recalling moves (for both themselves and others in their household) and move dates accurately because 11.6% of the population changed residences between March 2010 and February 2011 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2011). For the 2010 Census, the U.S. Census Bureau made the assumption that respondents could accurately remember moves and move dates on and around April 1 up to 11 months after April 1.

1.1 Memory for Moves

Memory of events is influenced by the recency of the event, the importance of the event to the respondent, whether the respondent has had to recall the event before, in addition to other biological factors such as the clarity of memory or the age of the respondent (Bradburn, Huttenlocher, and Hedges, 1994, Tourangeau, Rips, and Rasinski, 2000). These factors can influence a respondent’s tendency to forget the event or telescope the event.

Telescoping is a type of recall error where events are reported as happening either more recently than they actually happened (forward telescoping) or farther back than they actually occurred (backwards telescoping). Studies aimed at determining whether the net effect of recall errors is zero or tends toward backward or forward telescoping have frequently concluded that although there can be backwards telescoping, the net effect is most often forward telescoping of events (Neter and Waksberg 1964, Rubin and Baddeley 1989, Huttenlocher, Hedges, and Bradburn 1990, Janssen, Chessa, and Murre 2006). This tendency is due to a variety of factors including weak bounding criteria and the inability to backward telescope future events. Many of these studies asked for recall periods of 2 months, or 4 months or slightly longer. Janssen et al. (2006) found that dates of events in the news that occurred 1000 days or more prior to the study were more likely to be telescoped forward. However, events that occurred between 100 to 1000 days prior to the study were more likely to be backwards telescoped and no telescoping effect occurred for reporting dates of recent events occurring less than 100 days ago.

The census and its evaluative operations need to accurately identify who lived at each address on April 1st. If telescoping the move month or forgetting to recall a move increases as the interview date gets farther away from the move, then data collected months after April 1st may be problematic. The study of recall error associated with move dates is limited. Aurait (1993) examined the accuracy of reporting residential mobility using a study of 500 married couples aged 41 to 57 years old in Belgium. Comparing their residential mobility reports to Belgium’s National Population Register data, Aurait found dating errors for moves occurred in years more so than months. She also found that the birth of a child within a year or two of the move decreased dating errors for moves. Aurait found no net effect of telescoping of the move events in her analysis. Other survey methodologists have made similar assumptions about the quality of respondents’ recall of move dates. Move dates and places of residence often serve as anchors to aid memory of other events, particularly as part of the survey research technique that creates an event history or timeline (Belli, 1998; van der Vaart, 2004).

1.2 Data Quality in Proxy Reports

There is evidence in the literature that reports may also differ by the type of respondent – whether a self-report or proxy report. Miller, Massagli, and Clarridge (1986) examined quality of proxy versus self reports to twenty health questions asking specifically about health complaints, finding that proxy reports typically underestimated the health complaints even in serious situations. In studies of proxy data following the Census 2000, item non-response was lower when responses were provided by household members versus proxies such as neighbors, postal workers or landlords (Chesnut, 2005; Wolfgang, Byrne & Spratt, 2003). In a study looking specifically at coverage issues, Martin (1999) examined proxy-reporting errors for the concept of “usual residence.” She found that proxy reports of “usual residence” increased undercoverage for young black males in particular. Surrounding the 2010 Census, King, Cook and Childs (2012) examined self versus proxy reporting of living situation information, finding that self-report respondents provided more complete information than proxy respondents did. Though they reacted in different ways (self-reports refused questions and sometimes failed to provide requested information and proxies commented on sensitivity of questions), both showed evidence of privacy sensitivities that often revealed itself in item non-response.

1.3 Current Study

The present study investigates recall error regarding move month and reports of a move with thoughts to planning for the timing of census and evaluative operations for the 2020 Census.

The study compares independent survey responses of moves and move dates with the U.S. Postal Service National Change of Address (NCOA) files of requests to forward mail in March and April of 2010 (U.S. Postal Service 2015). The approach uses binomial and multinomial analyses to investigate whether recall error increases as the length of time from the move increases while controlling for the type of respondent. We investigated three research questions:

- whether reporting a move is affected as the time lapse between the move and the interview increases;

- whether the accuracy of the reported move month and the direction of the error is affected as the time lapse between the move and the interview increases; and

- whether the accuracy of the reported residence where someone should be counted for the Census is affected as the time lapse between the move and the interview increases.

2. Research methodology

To study recall errors in reporting moves, we started with a sample of 13,500 households selected from a frame of movers. We then conducted an independent U.S. Census Bureau telephone survey with these movers over different time periods to determine whether memory of the move and the move date decayed over time.

The original frame of movers consisted of records from an extract of the National Change of Address (NCOA) file dated May 1, 2010. This file only contained records that had reported a change of address in either March or April of 2010 submitted by May 1, 2010. While it is possible that for some of these records, the person submitted a “change of address” filing simply to forward mail to another address for a reason other than a physical move, for our purposes they were all classified as moves. Those who moved in March or April of 2010 but completed the United States Postal Service form after May 1 are not part of this analysis.

A systematic sample of sorted NCOA records was matched to a commercial database in May 2010 to obtain a telephone number for the address where the mail was forwarded. Then, addresses for which telephone numbers were found were randomly divided into three equal subsamples. Each subsample was contacted by telephone at a different interval after the move to determine whether they would report the move and if they reported the move whether there were recall errors in the reported move month. Appendix 1 contains more details of the sampling.

The Census Bureau survey was called the Recall Bias Study (RBS) (Linse, Pape, Rosenberger, and Contreras 2012). The interview timing for the three subsamples approximated the timing of 2010 Census and evaluative operations: June 2010, September 2010, and February 2011. Using AAPOR Response Rate 2 (American Association of Public Opinion Research 2011) that includes sample units of unknown eligibility in the denominator, response rates ranged from 63 to 69 percent.

The RBS instrument collected a roster of people currently living in the contacted housing units, other addresses where a person could have been counted around Census Day, April 1, 2010, and move dates associated with those other addresses, including month, day and year. The respondent was a member of the current household who was 18 years or older. This may or may not have been the person in the household whose name was on the NCOA form. Thus, respondents could self-report a move, or could report a move of another household member.

Our research strategy relies on assuming that the month to begin forwarding mail on the NCOA form is the ‘true’ move month. While this assumption is also a limitation in that there are reasons a person would forward mail to an address prior to, or after, the actual move month, this failure of the underlying assumption should affect the estimation for all levels of variables at the same rate. With this assumption, we are able to study recall bias in the RBS. We study forgetting to report a move by comparing the absence of a move report in the RBS to those moves reported in the NCOA. We study telescoping and the accuracy of move reports by comparing the reported month of the move in RBS to the NCOA month. The difference in the reported month and the NCOA month provides data to look for patterns of forward or backwards telescoping. Since many moves occur on the first of a month, we built in a tolerance by considering a RBS response of one month and the NCOA record having the last day of the previous month or the first day of the next month as agreeing. We use binomial and multinomial analyses to study the effects of the length of time between the “true” move and the survey interview, the respondent, and other characteristics of the move. These characteristics include whether the move was for a family or an individual (collected on the NCOA form) and, in a multi-person household, whether the report was a self or proxy response. These variables are of interest because they could yield practical information interviewers (or survey designers) could use to identify which respondent to interview to maximize the accuracy of move data. Appendix 2 contains detailed methodology.

Although the initial sample size was 13,500 households, we had to restrict our analyses to the datasets of size 3,424 households who reported the address and name that was on the NCOA form and 1,740 households who reported a move to the NCOA address and a date of that move. Appendix 1 discusses in detail the reasons for the loss of cases for the analysis.

3. Results

For our analysis, we explore the differences in the observed probabilities of accurately reporting a move or move month between the levels of the variables Interview Month and Respondent Type to examine the net effect on recall error. The variable Interview month reflects length of time since the move and could be June, August, or February, corresponding to length of time from Census Day – roughly, 2, 5 and 10 months from Census Day. Respondent Type is a three-level variable that combines the respondent type and the move type:

- Self – the respondent’s name is on the NCOA record and can be considered a self response;

- Family other – the respondent’s name is not on the NCOA record, but the record indicates it is a family move and the respondent is in multi-person household, so most likely the respondent moved, but we are not certain; and

- Individual proxy – when the respondent’s name is not on the NCOA record, but the record indicates there was an individual move – thus this is a true proxy situation.

These variables are detailed in Appendix 2 while the details of the statistical tests are in Appendix 3.

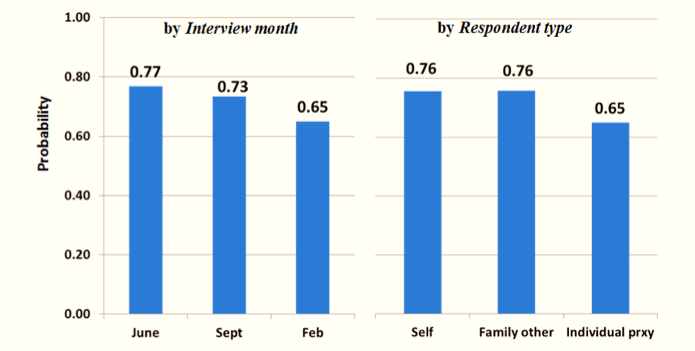

3.1 Memory of the Move

The first analysis focuses on the accuracy of survey reports of a move using the variable Move (presence or absence of a reported move) for 3,424 RBS respondents. The distribution of the respondents across months is 1,342 in June; 1,182 in September, and 900 in February. Chi-square tests show a statistical relationship between Move and Interview Month and between Move and Respondent Type, with an adjusted p-value equal to 0.003. Figure 1 shows the observed probabilities of accurately reporting a move by the length of time since the move corresponding to the levels of Interview Month and by the levels of Respondent type.

The graph in Figure 1 suggests a decrease in the probability of reporting a move as time from the move increases. The difference of 0.020 (SE=0.019) between the accuracy of reports by March and April movers answering in June and those answering in September is not statistically significant with the adjusted p-value of 1.000. However, the difference between the observed probabilities for June and February is 0.132 (SE=0.021) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003, and the difference between the observed probabilities for September and February is 0.112 (SE=0.022) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003. Therefore, the data indicates that March and April movers are less likely to report a move 10 months after a move than with shorter recall periods.

In Figure 1 Family other respondents have the largest probability of reporting a move, followed by Self reporting respondents, and Individual proxy respondent. The difference between the observed probabilities of a Family other respondent and a Self respondent reporting a move is -.095 (SE=0.020) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003 indicating that Family other respondents are more likely to report a move than Self respondents. In multi-person households, the difference between the observed probability of a Family other respondent and an Individual proxy is 0.177 (SE=0.020) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003 indicating that Family other respondents are more likely to report a move. The difference in the probability of reporting a move for an Individual proxy and a Self report is 0.082 (SE=0.023) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003 indicating that an Individual proxy is less likely to report a move by another household member than a Self respondent.

Figure 1. Observed probability of accurate reports of moves in March and April 2010 (Move) by length of time since move (Interview month) and by respondent type (Respondent type)

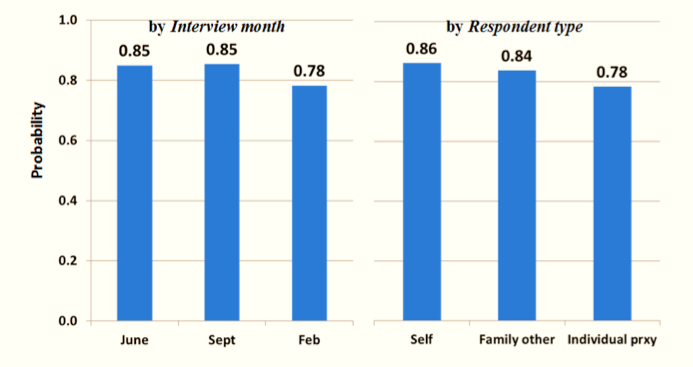

3.2 Memory of the Move Date

The next analysis focuses on the accuracy in reporting a move month using the variable NoBias (agreement or disagreement of move month between the survey and the NCOA record). The 1,740 RBS responses that reported a move to the NCOA forwarding address with the date are distributed across interview months with 760 in June; 611 in September, and 369 in February. Chi-square tests show a statistical relationship between NoBias and Interview Month and between NoBias and Respondent Type, with an adjusted p-value equal to 0.003. Figure 2 shows the probabilities of the reported move month agreeing with the NCOA month by length of time since the move corresponding to the levels of Interview Month and Respondent Type.

Figure 2. Accuracy rate in reports of move month for movers in March and April 2010 (NoBias) by length of time since move (Interview month) and by respondent type (Respondent type)

The difference in the observed probabilities for June and September is 0.034 (SE=0.024) with an adjusted p-value of 1.000 and the difference between the probabilities for June and February is 0.118 (SE=0.029) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003. The difference between the probabilities for September and February is 0.085 (SE=0.031) with an adjusted p-value of 0.084. Therefore, the evidence indicates that March and April movers are less likely to report an accurate move month 10 months after Census Day than 2 months afterwards, and are less likely to report an accurate move month 10 months after Census Day than 5 months afterwards. The data does not detect a difference in accuracy of responses between 2 and 5 months after Census Day and that the error in the recall of the move month increases between 5 and 10 months after Census Day.

The difference in the probabilities of agreement between the reported month of a move and the NCOA record for a Self respondent and for a Family other respondent is -0.002 (SE=0.024) with an adjusted p-value of 1.000. However, the difference in the probabilities for a Self report and an Individual proxy is 0.105 (SE=0.028) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003. The difference in the probabilities of agreement for a Family other respondent and an Individual proxy is 0.108 (SE=0.031) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003. These results indicate that agreement between the reported and NCOA move months is more likely for a Self report and a Family other respondent than an Individual proxy. In addition, the data indicate that agreement in reported and NCOA move months is equally likely for moves by a Family other respondent and by a Self respondent.

3.3 Effect of Memory Error on Accuracy of Census Enumeration

We examine the effect of recall error on the reporting of Census Day residence using the variable SameSide (whether the reported date of the move in the survey and in the NCOA were on the “same side” of Census Day or not) and the same 1,740 responses used in the analysis of NoBias. Chi-square tests show a statistical relationship between SameSide and Interview Month with an in adjusted p-value equal to 0.084, and between SameSide and Respondent Type with an adjusted p-value of 0.040. Figure 3 shows the probabilities of agreement between the reported and NCOA Census Day residence month by length of time since the move corresponding to the levels of Interview Month and household move type corresponding to the levels of Respondent Type.

Figure 3. Observed probability of accurate reports of Census Day address for movers in March and April 2010 (SameSide) by length of time since move (Interview month) and by respondent type (Respondent type)

The difference in the probabilities of agreement between the reported and NCOA Census Day residence for June and September is -0.004 (SE=0.019) with an adjusted p-value of 1.000, and the difference between June and February is 0.067 (SE=0.025) with an adjusted p-value of 0.088. Therefore, there is no evidence that the reports from March and April movers are more or less likely to be on the same side of April 1 when the elapsed time is five months after Census Day than two months afterwards. However, the evidence indicates responses 2 months after Census Day are more likely to be on the same side of April 1 than responses 10 months afterwards. In addition, the difference between the probabilities for September and February is 0.071 (SE=0.026) with an adjusted p-value of 0.084. Therefore, responses from March and April movers are more likely to be on the same side of Census Day five months retrospectively than 10 months retrospectively. These differences imply that there would not be any more error in enumeration for movers five months after Census Day than there was two months after Census Day; however, there would be more error in enumeration of movers 10 months after Census Day. This type of evidence raises a concern for the Census and its evaluations if they are conducted 10 months or more after Census Day.

The difference in the probabilities for a Self report and an Individual proxy is 0.078 (SE=0.024) with an adjusted p-value of 0.003 indicating that an Individual proxy is less likely to report an accurate Census Day address for movers than a Self reporter. The difference between the probabilities for a Family other respondent and Individual proxy in a multi-person household is 0.054 (SE=0.026) with an adjusted p-value of 0.378 while the difference in probabilities for a Self respondent and a Family other respondent is 0.025 (SE=0.02) with an adjusted p-value of 1.000. Consequently, there is no evidence that a Family other respondent is more or less likely report an accurate Census Day address for movers than a Self reporter or an Individual proxy.

3.4 Telescoping of Move Dates

Now we turn our attention to investigating whether the net effect of recall error in move month tends to be backwards or forwards as the time since the move increases, or whether the errors tend to cancel each other out using the variable Recall Bias, which has three defined levels, forward, backward or no change. For this analysis, we use the same 1,740 responses used in the analysis of NoBias and SameSide. Figure 4 provides some insight by showing a bar graph of the observed conditional probabilities Interview month within Respondent type. We decided not pursue testing with the data from the Family other respondents due to low observation numbers in February for forwards and backwards telescoping. Cells with small numbers of observations tend to produce unstable p-values. Adjusted p-values for chi-square tests show a statistical relationship between Recall Bias and Interview month for Self reports (adjusted p-value = 0.002) but not for Individual proxies (p-value = 0.175) so we did not conduct tests between the levels of Interview month for Individual proxies.

For Self respondents, the observed forwards and backwards probabilities shown in Figure 4 are very close to each other and stable in June and September. Then both observed probabilities increase in February, but the observed backwards probability appears to have a larger increase. We conducted statistical tests by comparing the observed probabilities of backward to forward telescoping for each interview month by calculating the difference. For Self respondents difference in the direction of the errors in June and September is not significant with the adjusted p-values, implying the errors offset each other two months or five months after Census Day. The adjusted p-value of 0.105 does not indicate that backward telescoping is greater than forward telescoping in February. Therefore, for 10 months after Census Day, the evidence does not meet conventional scientific standards to indicate the error is greater in one direction that another.

Figure 4. Observed Conditional Probabilities of backwards telescoping, zero error, and forwards telescoping in reports of move month by type of respondent and interview months. Cell sizes are shown on the bars.

4. Conclusions

Our experiment proved the feasibility of using NCOA records as a source of administrative records for movers to study recall error in survey reports of moves and move months. Due to the limited amount of data that was usable for this study, results are limited. Future studies should seek to conduct interviews in person at the destination address on the NCOA form. This would avoid the inability to link to a telephone number to the correct address and resident. In situations where the person listed on the NCOA form does not live at the reported address, the interviewer should ask whether the person ever lived there. Training interviewers on the importance of collecting the date of the move to the destination address also would reduce loss of cases. In addition, designing a study in a manner that anticipates the need for suitable population controls for movers would make weighting possible and strengthen the data analyses.

Though limited, our analysis showed the length of time since the move and the respondent type affect the accuracy of survey reports of a move and the reported move month. The study found a large decline in accuracy 10 months after the move in the reporting of the move, the move month, and the Census Day address. Even though memory of move month decays over time, the census would only be affected partially by this decay because of the need for the move to be reported on the “correct side” of Census Day.

Accuracy also differed by who moved in the household and who reported the move in a way that was consistent with other research on proxy reporting. Proxy reports about individual movers within the household were always the least accurate. Family move reports (these are situations when the respondent might or might not have moved with the family) and self-reports (when the respondent was the mover) were always more accurate than proxy reports about an individual mover.

When viewing the results, one must be mindful of the limitations in using NCOA file as a source for movers as well as the limitations of the data collection in this study. The NCOA file does not contain all move reports because many movers do not file a request to forward mail. It is plausible that some of the NCOA records may have reflected people who moved prior to January 1, 2010 and were late to file a NCOA request. It is difficult to fathom that 43% of self-respondents forgot to report their residential move in the survey. It could be that even though these persons filed a change of address, they did not physically move (they just changed where they got their mail) or they moved prior to January 1, 2010. In addition, we were only able to link 20% of addresses to a telephone number even though all of the sample addresses in the study were residential. In spite of the data limitations, the results of this analysis contribute to the knowledge regarding the accuracy of survey reports of moves and the nature of the recall error.

The results of our investigation regarding the direction of the error in self-reports of move month imply the errors offset each other 2 and 5 months after a move. However, the smaller number of observations in February appears to have hampered our investigation into the direction of the error in the reported move month. Therefore, our results regarding direction of reporting error 10 months after a move are inconclusive. One might say our results more closely parallel those of Auriat (1993) who did not find telescoping in her analysis than those of Janssen et al. (2006) who detected backward telescoping 100 to 1,000 days after the event and no telescoping effect less than 100 days after an event. Auriat asked respondents about more salient topics than the news events used by Jansen et al., which might account for the similarity of our results and Auriat’s. However, another possibility is that the design of the RBS questionnaire was effective enough in aiding recall to extend the length of time before backwards telescoping begins. Further research is needed regarding the direction of reporting error and to determine whether the starting point and direction of telescoping varies by the characteristics of the respondent, the nature of the event, length of time since the event, and the design of the questionnaire. With more knowledge about the factors that influence the beginning of backwards telescoping, researchers will be able to design surveys in a manner that reduces the effect of recall error on results.

Appendix 1. Data limitations

Appendix 2. Detailed Methodology

Appendix 3. Statistical tests for observed differences

References

- Auriat, N. (1993). “My wife knows best”: A comparison of event dating accuracy between the wife , the husband, the couple, and the Belgium population register. Public Opinion Quarterly, 57 (2): 165-190.

- American Association for Public Opinion Research. (2011). Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 7th edition. AAPOR. http://www.aapor.org/AAPORKentico/AAPOR_Main/media/MainSiteFiles/StandardDefinitions2011_1.pdf (Accessed February 6, 2015).

- Belli, R. F. (1998). The structure of autobiographical memory and the event history calendar: Potential improvements in the quality of retrospective reports in surveys. Memory, 6, 383-406.

- Benetsky, M. J., Burd, C. A., and Rapino, M. A. (2015). Young Adult Migration 2007 to 2009 and 2010 to 2012 American Community Survey Report ACS-31. U.S. Census Bureau.Washington, DC. http://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2015/acs/acs-31.pdf?eml=gd&utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery (Accessed April 1, 2015).

- Bradburn, N., Huttenlocher, J., & Hedges, L. (1994). Telescoping and temporal memory. In N. Schwarz, & S. Sudman (Eds.), Autobiographical memory and the validity of retrospective reports (pp. 203–215). New York: Springer-Verlag.

- Chesnut, John (2005). “Item Nonresponse Error for the 100 Percent Data Items on the Census 2000 Long Form Questionnaire,” ASA Section on Survey Research Methods, Joint Statistical Meeting, Minneapolis, Minnesota, August 2005.

- Diffendal, G. and Moldoff, M. (2010). 2010 Census Coverage Measurement Recall Bias Study – National Change of Address File Sample. DSSD 2010 CENSUS COVERAGE MEASUREMENT MEMORANDUM SERIES #2010-I-08. U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC.

- Griffin, R. (2011). 2010 Census Coverage Measurement Survey Recall Bias Study: Weighting and Variance Estimation. DSSD 2010 CENSUS COVERAGE MEASUREMENT MEMORANDUM SERIES #2010-I-11. U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC.

- Hansen, K. A. (1998) Seasonality of Moves and Duration of Residence. Current Population Report P70-66. U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC. https://www.census.gov/sipp/p70s/p70-66.pdf (Accessed March 3, 2015)

- Huttenlocher, J., Hedges, L.V., and Bradburn, N.M. (1990). Reports of elapsed time: Bounding and rounding processes in estimation. Journal of Experimental Psychology, Learning. Memory, and Cognition, 16, 196-213.

- Janssen, S., Chessa, A., and Murre, J. (2006). Memory for time: How people date events. Memory & Cognition. 34(1). 138-147.

- Johnson, N. and Kotz, S. (1969) Discrete Distributions. Wiley. New York, NY.

- King, T., Cook, S., and Childs, J.H. (2012). Interviewing Proxy Versus Self-Reporting Respondents to Obtain Information Regarding Living Situations. Proceedings for the Joint Statistical Meetings, Survey Research Methods Section. https://www.amstat.org/sections/srms/proceedings/y2012/files/400243_500698.pdf (Accessed May 23, 2016).

- Linse, K., Pape, T., Rosenberger, L., and Contreras, G. (2012). 2010 Census Coverage Measurement Survey Recall Bias Study. DSSD 2010 CENSUS COVERAGE MEASUREMENT MEMORANDUM SERIES #2010-I-22. U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC.

- Martin, E. (1999). “Who Knows Who Lives Here? Within-household Disagreements as a Source of Survey Coverage Error,” Public Opinion Quarterly 63: 220-36.

- Miller, R.E., Massagli, M.P., & Clarridge B. (1986). “Quality of Proxy vs. Self-Reports: Evidence from a Health Survey with Repeated Measures.” American Statistical Association, Proceedings of the Section on Survey Research Methods.

- Moore, J. C. (1988). Self/Proxy Response Status and Survey Response Quality: A Review of the Literature. Journal of Official Statistics, 4(2) 155-172.

- Moore, J. C. (2010). Proxy Reports: Results from a Record Check Study. Statistical Research Division Research Report Series (Survey Methodology #2010-09).

- Neter, J. & Waksberg, J. (1964). A study of response errors in expenditure data from household interviews. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 59, 18-55.

- Rubin, D.C. & Baddeley, A. D. (1989). Telescoping is not time compression: A model of the dating of autobiographical events. Memory and Cognition, 17 (6), 653-661.

- SAS Institute, Inc. (2009). SAS 9.2 Documentation. SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC.

- Tourangeau, R., Rips, L. J., & Rasinski, K. (2000). The psychology of survey response. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ Press.

- U.S. Census Bureau (2011) Geographic Mobility 2010 to 2011. U.S. Census Bureau. Washington, DC. https://www.census.gov/hhes/migration/data/cps/cps2011.html (Accessed May 23, 2016).

- U.S. Postal Service. (2015). NCOALink. U.S. Postal Service. Washington, DC. https://ribbs.usps.gov/index.cfm?page=ncoalink (Accessed February 6, 2015).

- Van der Vaart, W. (2004). The Time-line as a Device to Enhance Recall in Standardized Research Interviews: A Split Ballot Study. Journal of Official Statistics, 20 (2), 301-317.

- Westfall, P., Tobias, R., Rom, D., Wolfinger R. and Hochberg, Y. (1999). Multiple Comparisons and Multiple Tests Using SAS. SAS Institute, Inc.. Cary, NC.

- Wolfgang, G., Byrne, R., and Spratt S. (2003). Analysis of Proxy Data in the Accuracy and Coverage Evaluation. Census 2000 Evaluation O.5. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau.