Editorial – Advancing Comparative Research: Toward a Methodological Framework for Valid Comparative Inference

Leitgöb, H., Kley S., Meitinger K.& Menold N. (2026). Advancing Comparative Research: Toward a Methodological Framework for Valid Comparative Inference. Survey Methods: Insights from the Field, Special issue ‘Advancing Comparative Research: Exploring Errors and Quality Indicators in Social Research’. Retrieved from https://surveyinsights.org/?p=21974

© the authors 2026. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

Abstract

This editorial presents ideas for a comprehensive quality framework for survey-based comparative research to improves the validity of comparative inferences. We synthesize insights from causal inference validity, research on bias in cross-cultural measurement, the total survey error perspective, test and measurement theory, and the estimands approach. With a particular emphasis on measurement-related aspects, the editorial reflects the thematic focus of the contributions in this special issue.

Copyright

© the authors 2026. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CC BY 4.0)

1. Introduction

Since the onset of the discipline, the comparative method has been regarded as a defining principle of the social sciences, as expressed by Durkheim (1982 [1895], p. 157): “Comparative sociology is not a special branch of sociology; it is sociology itself.” This ubiquity is evident, among other things, in counterfactual causal reasoning (e.g., Collins et al., 2004), which is based on comparing an outcome of interest in a world where units receive some treatment with the outcome that would have occurred in a counterfactual world without that treatment, all else equal.

Since the mid-20th century, surveys have become a primary data source for social science research (Groves et al., 2009) and large-scale cross-national survey programmes, educational assessments, and longitudinal studies have been developed to enable systematic comparisons of social phenomena across countries, cultural contexts, regions, population groups, and over time. Beyond the mere identification of contextual or temporal differences, these comparative survey data contribute to the generation, testing, and further development of social science theory (Kohn, 1987). This is particularly true for the understanding of the impact of contextual factors on individual characteristics and behavior, as well as the processes of social change (Meuleman et al., 2018).

To ensure the validity of inferences drawn from comparative research, survey data used for comparisons must satisfy several criteria. This special issue seeks to examine these conditions and to highlight recent advances, challenges, and best practices in achieving valid comparative inferences. To this end, this editorial aims to lay the methodological groundwork by proposing ideas of a comprehensive quality framework for survey-based comparisons. To do so, we draw on concepts of validity of causal inferences (Shadish et al., 2002), exploration of bias in cross-cultural research (e.g., van de Vijver, 2018; van de Vijver & Poortinga, 1997), the survey life cycle model from the total survey error framework (Groves et al., 2009), causal graph theory (e.g., Pearl, 2009), as well as test and measurement theory (Lord & Novick, 1968; Markus & Borsboom, 2025; Muthén, 2002).

The remainder of this editorial is structured as follows: Section 2 lays out basic ideas for a methodological foundation for the survey-based comparative inference. Section 3 focuses on the core topic of this special issue, the measurement-related aspects of comparisons. Finally, Section 4 offers concluding reflections and a brief outlook.

2. Methodological Foundations of the Validity of Comparative Inferences

Following the four types of validity for causal inference proposed by Shadish et al. (2002), a comprehensive framework for survey-based comparative inference should, at a minimum, incorporate (i) construct, (ii) internal, (iii) statistical conclusion, and (iv) external validity as core components. As previously outlined, this framework is based on a special case of comparison, typically involving differences in outcome means between treatment and control groups in (quasi-)experimental designs. However, the far-reaching ceteris paribus assumptions underlying these causal settings do not apply to comparative analyses in general. For comparative survey data, this framework needs to be extended to explicitly include equivalence assumptions to support the validity of comparative inferences.

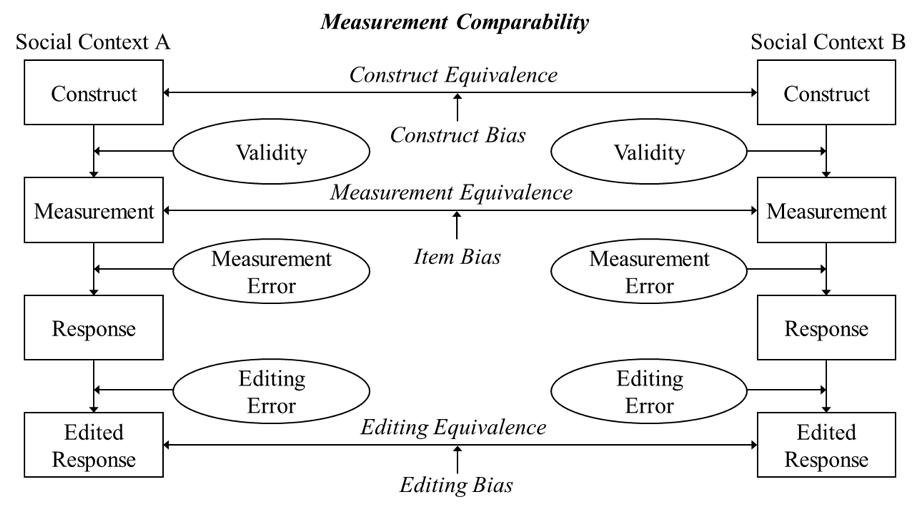

Starting with (i) construct validity (Lord & Novick, 1968), theory provides the conceptual foundation for the constructs under investigation, which require a precise definition and specification of concepts, followed by their appropriate operationalization and measurement to bridge the theoretical and the empirical worlds (e.g., Saris & Gallhofer, 2014). In the comparative case, construct validity—that is, the degree to which the operational measures are related to the constructs as originally intended—must be complemented by construct and measurement equivalence assumptions. The former reflects that a theoretical construct requires not only an adequate definition and conceptualization within each social context under comparison, but also the same conceptual meaning across all contexts. Otherwise, apples are literally compared with oranges (Stegmueller, 2011), thereby introducing construct bias (e.g., van de Vijver, 2018; van de Vijver & Poortinga, 1997), which jeopardizes the ability to draw substantive conclusions about differences, their causes, and their consequences. A prominent example is the culturally divergent understanding of “happiness”, which is interpreted as an individual achievement in some cultures and as interpersonal connectedness in others (Uchida et al., 2004). We rely on the measurement part of the survey life cycle model within the Total Survey Error (TSE) paradigm (Groves et al., 2009) to illustrate the relationship between construct equivalence, measurement and validity assurance (Figure 1).

The measurement equivalence assumption, as implemented in Figure 1, implies that the indicators used to observe a theoretical construct (e.g., items in a survey instrument or a psychological test) capture that construct in a comparable manner, without idiosyncratic measurement error and with similar level of precision across the social contexts or time points under comparison (Leitgöb et al., 2021, 2023). If this assumption is violated, item bias (e.g., van de Vijver, 2018; van de Vijver & Poortinga, 1997) arises, meaning that observed response differences reflect—at least in part—measurement artifacts stemming from properties or presentation of the indicators rather than true differences in the underlying construct (see Section 3).

The conceptualization of theoretical concepts as latent constructs (Bollen, 2002) is formalized in measurement models that specify the relationship between latent variables and their manifest indicators. Once the measurement structure has been determined theoretically as reflective or formative (e.g., Bollen & Bauldry, 2011; Bollen & Lennox, 1991; Meulemann et al., 2023; Welzel et al., 2023), a statistical model can be specified to assess whether the implied measurement and equivalence assumptions are supported by the comparative data at hand.[1] While confirmatory factor analysis (CFA; grounded in classical test theory; Lord & Novick, 1968) and item response theory (IRT; Lord 1980) models are standard frameworks for reflective measurement, formative specifications are typically implemented via index construction and composite-based estimation rather than through axiomatic latent variable theory. A key advantage of CFA and IRT models is that they entail testable implications for whether the underlying measurement axioms and equivalence assumptions hold empirically (e.g., Markus & Borsboom, 2025).[2] Consequently, these modeling approaches allow researchers to diagnose violations with respect to construct and measurement equivalence, separate substantive variance from measurement error, and detect potential scaling nonequivalence across units of comparison. This supports more defensible estimates of differences while flagging threats to the statistical conclusion validity of comparative inferences (see Section 3). Such tests are limited in formative specifications, because the indicators are treated as constituent causes of the construct and therefore need not be interchangeable or exhibit the correlation patterns implied by reflective models. Instead, formative constructs must be embedded in a nomological network in which external criteria—specified as causal consequences of the construct—support identification and provide evidence for validity (Bollen & Bauldry, 2011; Bollen & Lennox).

Building on Groves et al. (2009), one may—for completeness—also consider response editing. The underlying editing equivalence assumption posits that no systematic differences in editing errors occur across the social contexts under comparison, and violations of this assumption lead to editing bias.

Taken together, these considerations form the basis of the measurement comparability framework illustrated at the center of Figure 1 for the simple two-context case.

Figure 1: Measurement comparability

Notes: The Figure is based on the measurement path of the survey life cycle model as illustrated in Figure 2.5 in Groves et al. (2009, p. 48).

The next forms are internal and statistical conclusion validity. (ii) Internal validity, generalized to comparative (including non-causal) inference, concerns whether substantive cross-group or temporal (non-)differences of interest can be validly inferred from the data at hand, that is, whether the data allow true underlying (non-)differences to be accurately recovered. (iii) Statistical conclusion validity, as applied to general comparative inference, refers to the degree to which statistical evidence credibly supports the conclusion that the compared units differ in the quantities of interest beyond what would be expected by chance. Its adequacy rests upon the rigor of the employed analytical strategy and the extent to which it addresses the underlying (equivalence) assumptions to ensure that observed differences are not merely statistical artifacts. Beyond the selection of adequate statistical models and tests, this further entails attention to scaling metrics and the systematic handling of measurement error.

Finally, (iv) external validity concerns the generalizability of inferences through extrapolation (Shadish et al., 2002). Within a general comparative framework, it addresses the extent to which inferences derived from comparative findings hold under variations in mechanisms, (comparison) units, settings, measures of the social phenomena under study, and time. This perspective can be understood as a non-causal adaptation of the M-STOUT framework (mechanisms, settings, treatments, outcomes, units, time; e.g., Findley et al., 2021), which itself extends the traditional UTOS components (units, treatments, observations, settings; Cronbach & Shapiro, 1982; Shadish et al., 2002) by incorporating mechanisms and time as additional dimensions for defining the scope conditions that bound an inference.

Current approaches differentiate between generalizability and transportability as distinct facets of external validity. While generalizability refers to the validity of an inference from a sample to the underlying target population (e.g., Findley et al., 2021; Lesko et al., 2017), transportability refers to extending inferences from a sample to other non-overlapping populations or situations and therefore requires additional assumptions to justify cross-population extrapolation (Findley et al., 2021, p. 369; see also Pearl & Bareinboim, 2014).

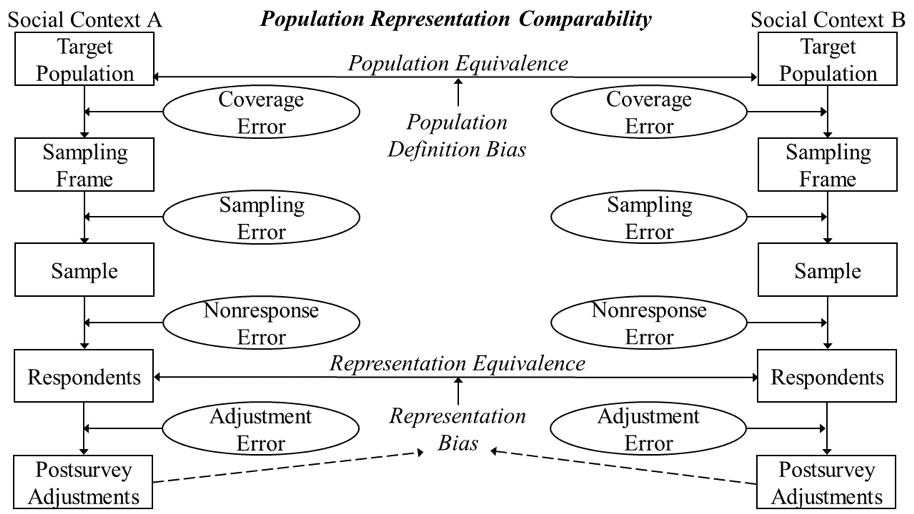

For the survey context, generalizability implies that the social contexts being compared must either be based on an identical definition of the corresponding target populations (e.g., all persons aged 15 and over residing in private households in each country participating in the European Social Survey; ESS Sampling Expert Panel 2016, p. 5) or constitute well-defined subpopulations of a common target population (e.g., gender groups from a country’s target population as defined in the ESS).

If target population equivalence is violated, observed cross-context differences may reflect discrepancies in the population definition criteria rather than substantive variation, introducing what we refer to as population definition bias (see Figure 2). Importantly, the assumption does not imply that the populations in all comparison units have identical compositions (e.g., equivalent age or gender distributions), but rather that they are based on the same definitional framework. A violation would occur, for example, in a comparison of adolescent criminality if “adolescents” were defined as ages 10 to 16 in country A but 12 to 18 in country B. Because older adolescents typically exhibit higher offending rates, differences in reported juvenile crime between these two countries could arise solely from these non-equivalent age definitions rather than from true behavioral differences.

Next, we turn to the comparability of the context-specific net samples—that is, the outcomes produced by the data generation process, spanning population coverage, sampling, and survey participation along the representation path of the survey life cycle of the TSE model (Groves et al., 2009; see Figure 2). The underlying assumption is representation equivalence, meaning that the net samples across comparison units are equivalent in how well they represent the respective target populations. Under ideal survey conditions, deviations between the achieved sample and the population compositions occur only at random (e.g., through random coverage or sampling error, or missingness that is completely at random), implying that observed and statistically tested differences in social phenomena of interest reflect genuine population differences. When representation equivalence is violated, systematic representation bias arising from differential coverage, selection, or participation mechanisms may generate artificial differences or obscure real ones. For example, observed cross-country differences in income distributions from online surveys may be biased when digital access—especially among low-income groups—varies substantially across countries, undermining the validity of conclusions about income inequalities. This bias may persist after postsurvey adjustment (e.g., through poststratification weighting) or may even be introduced by the adjustment itself.

Summing up, target population and representation equivalence constitute core assumptions that, when satisfied, underpin the external validity of comparative inferences by ensuring that net samples across comparison units both align in their definitions and are equally representative.

Figure 2: Population representation comparability

Notes: The Figure is based on the representation path of the survey life cycle model as illustrated in Figure 2.5 in Groves et al. (2009, p. 48).

Within the general comparative framework proposed here, both variants of external validity necessitate that the structural properties of an inference remain stable across contexts. However, transportability imposes the additional requirement of substantiating the cross-population invariance of the mechanisms generating the measurement and relational structures when extending inferences to new units or settings.

Having elaborated on this framework for the validity of general comparative inference based on survey data, we will now turn to measurement comparability—the core focus of this special issue and a cross-cutting cornerstone that permeates all these components of validity.

3. Measurement Comparability

Measurement in social science surveys aims to provide operationalizations of terms and concepts included in social science theories (Groves et al., 2009). The overarching objective of measurement is therefore to generalize from the observed data to theoretical concepts, referred to in the measurement literature as latent variables (Bollen, 2002)—such as individualism, authoritarianism, pro-democratic opinions, pro-social behavior, political trust or well-being. Besides few factual questions, the main goal of measurement in the social sciences and related disciplines is to link observed or manifest indicators—that is, the survey questions or statements evaluated by respondents—to the underlying theoretical concept conceived as a latent variable (as shown in Figure 1). As the aim is to observe the unobservable, a theory and methodology for relating observed indicators to latent variables are crucial. Such a background is provided by measurement and psychometric theories which include epistemological frames with—ideally—testable assumptions about the observable outcome of the measurement process.

Latent variable modeling (LVM) redirects the fundamental question in survey measurement from “what is the measurement scale” to “what is the underlying measurement model” (Markus & Borsboom, 2025). The function of the measurement model is to postulate and specify the relationships between the latent and observed variables. For the purpose of validation, the precision and accuracy of the proposed measurement model must be addressed (Raykov, 2023; Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011). In reflective measurement models, precision corresponds to reliability in psychometric theory and is defined as the proportion of observed-score variance attributable to true-score variance (Lord & Novick, 1968). Accuracy addresses the validity of the measurement and general definitions include the appropriateness of conclusions drawn from obtained measurement scores (Messick, 1989) as well as the suitability of their use (Kane, 2013). Comparative research adds additional validity issues such as the adequacy of the conceptual link between the observed and the latent variables in each group included in the analysis (Zumbaro & Chan, 2014) as outlined above by introducing construct bias in the general framework (see Figure 1). Specifying and evaluating a measurement model provides a valuable theoretical frame and practical tool not only for the assessment of reliability and validity as criteria of measurement quality (Raykov & Marcoulides, 2011), but also for the empirical evaluation of comparability of the proposed measurement model in different groups and contexts such as countries and languages (Meredith, 1993). Therefore, the LVM framework represents a useful tool to evaluate both, construct and item equivalence (see Figure 1).

Unfortunately, social scientists rarely consider psychometric theories, measurement models, reliability or validity issues when developing, using or re-using questions and questionnaires as measurement instruments. Rammstedt et al. (2015) pointed out this lack of consideration ten years ago, and—with a few notable exceptions such as the European Social Survey (ESS) or the Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE)—the practice has hardly changed since then. Many large-scale social surveys lack documentation of which concepts are intended to be measured by which indicators, and with what measurement quality. When assessed by data users, reliability has often been found to be low or even unacceptable, as documented, for example, for the International Social Survey Program (ISSP) in measures of children stereotypes or for the European Values Study (EVS) in measures of gender role attitudes/stereotypes (Lomazzi, 2017; Menold et al., 2025). In addition, surveys sometimes incorporate instruments of low or unacceptably low reliability, as documented for several instruments in the ESS. For example, Cronbach’s Alpha of .50 is reported for the measurement of some instruments in several countries (Schwartz et al., 2015). Disregarding measurement reliability, or relying on instruments with low or even unacceptable reliability, strongly limits the usability of available data, as sufficient reliability is a prerequisite for meaningful and valid comparisons.

As a relevant validity issue, comparability bias should—and can—be empirically evaluated before interpreting statistical results on group differences to ensure the internal validity of the comparative conclusions from the obtained results. This exercise is necessary, because concept or item bias (van de Vijver, 2018, Figure 1) can occur and should be excluded as an alternative explanation of group differences under investigation. Due to developments in structural equation modeling (SEM), approaches for a straightforward evaluation of the measurement-related equivalence assumptions outlined in Section 2 are readily available (Leitgöb et al., 2023). The most commonly used LVM-based methods for multi-item measurement are measurement invariance tests implemented via multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (MGCFA, Meredith, 1993) and panel CFA for longitudinal comparisons (Leitgöb et al., 2021). More liberal alternatives include Bayesian approximate MGCFA/panel CFA (Muthén & Asparouhov, 2012; Seddig & Leitgöb, 2018a, 2018b; van de Schoot et al., 2013) and the alignment method (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2014).

The assessment of existing comparative data with these methods revealed disappointing results. Measurement invariance has frequently been rejected, particularly in the case of cross-cultural (Benítez et al., 2022; Davidov et al., 2008; Wu et al., 2007) or cross-ethnic (Dong & Dumas, 2020) comparisons. To the extent that the rejection of measurement invariance can be considered as an indicator of comparability bias, many available cross-cultural data are affected by it, which restricts the validity of large- and small-scale comparative research.

Since the early days of cross-cultural research, scholars have recognized the challenges of developing and translating instruments (Harkness, 2003). The LVM framework and measurement invariance testing strategies provide a powerful methodology to assess measurement problems and to conduct research on the sources of comparability bias. Several simulation studies revealed that comparisons are biased when measurement non-invariance is present as diagnosed by MGCFA-based global invariance testing and related methods (Kim et al., 2017; Meade & Lautenschlager, 2004; Pokropek et al., 2019; Yoon & Millsap, 2007). In addition, several pioneering mixed-method studies illustrated the association between measurement non-invariance and the cross-cultural differences in concepts and respondents’ understanding of questions. For example, measurement invariance was rejected in the study by Meitinger (2017) for the request to evaluate “pride in the social security system” of the respondent’s country, for which qualitative web probing also revealed systematic differences in the meaning of the “social security systems”. Benítez et al. (2022) evaluated measurement invariance in the Quality of Life measures in Dutch and Spanish for several cross-cultural surveys. The authors demonstrate that differences in the understanding of terms included in the questions and cross-cultural differences in cognitive processes were associated with the statistical non-invariance. Most recently, Menold (2025) provided several instances of concept and item bias for the comparisons of physical and mental health as well as Life Satisfaction measures between the German host and the Arabic refugee population, and revealed their association with non-invariance.

Overall, the research on comparability bias and its sources is in its infancy. We know relatively little about how to obtain comparable measures across different countries and cultures, and about the cultural, behavioral, or cognitive sources of incomparability. Our knowledge about which methodological decisions—for example in questionnaire design—can introduce method bias is limited as well (Menold, 2025; Menold et al., 2025). Many questionnaires and items are developed in Western societies and languages. Simply translating items without considering cultural, behavioral and cognitive backgrounds can be insufficient. However, promising conceptual refinements (e.g., Fischer et al., 2025) are emerging that can advance a more precise, cumulative understanding of comparability bias and its underlying mechanisms.

With this Special Issue, we invited survey researchers and practitioners to reflect on measurement quality and its associations with comparability bias in different survey contexts.

4. Overview of Special Issue Articles

As outlined above, sufficient reliability is a necessary condition for valid statistical comparisons in reflective measurement models. Because comparability bias and measurement equivalence are relatively recent research areas, the theoretical development and empirical research on the relationship between measurement reliability and measurement invariance remain limited. Raykov & Menold present a simulation study that examines whether small violations of measurement invariance affect comparisons of latent means between groups when reliability is reasonably high. The authors employ the concept of “maximal reliability” (e.g. Conger, 1980) to estimate reliability, which is particularly useful in social science measurement, where relatively short instruments with heterogeneous indicators are common.

As a core construct in social science research, almost every survey contains a measure of the highest level of attained formal education, yet measurement quality and comparability bias are rarely evaluated for this domain. The article by Schneider & Urban offers an innovative application of formative measurement models (e.g., Bollen & Bauldry, 2011; Bollen & Lennox, 1991; Edwards & Bagozzi, 2000), in which the education variable is used to predict variances in other variables. This contribution aims to evaluate the validity and cross-cultural comparability of education variables in the ESS and advances methods for diagnosing comparability issues in single-item measures.

Repke & Felderer address the role of language and cultural differences in measurement error. They ground their analysis in a measurement model within SEM and use an adaptation of the Multi-Trait-Multi-Method approach (Campbell & Fiske, 1959) as developed by Saris & Andrews (2004). The study is a meta-analysis that assesses cross-national and cross-linguistic differences in measurement error and also evaluates the link between measurement error and representation errors.

Finally, in his article, Wildfang draws attention to pitfalls in spatial comparisons of data collected from surveys and other data sources, illustrated through sensitivity assessments of segregation indices in two cities.

In a nutshell, the articles included in this Special Issue address challenging open research questions on comparability bias, its sources, and measurement. Taken together, they exemplify research in survey methodology that can strengthen the impact of cross-cultural or comparative survey research.

5. Outlook

This editorial intends to outline ideas for a broad methodological framework for conducting survey-based comparative research. The considerations offered here provide a basic conceptual structure that can be extended and elaborated in multiple directions. We conclude by offering directions to guide further work, building particularly on the estimands approach and graph-based causal reasoning.

Recently, Lundberg et al. (2021) argued for distinguishing between precisely defined theoretical and empirical estimands in causal inference to link statistical evidence with theory and thereby strengthen validity. Theoretical estimands consist of two components, the unit-specific target quantity and a well-defined target population to which the causal claim pertains. Empirical estimands are defined in terms of observable quantities and represent the information about the target quantity that can be learned from data. Both types of estimands are linked through identification assumptions, which should be explicitly stated as part of good scientific practice.

Again, this concept can be readily extended to non-causal comparisons, requiring some redefinition of the theoretical estimand and corresponding adaptations of the empirical estimand. First, the theoretical target quantities are typically differences in population parameters across comparison units in comparative research. These parameters are often means, but they may also be other moments of a distribution, measures of association, or causal effect parameters. Second, the definition of the target population refers to both, (i) the population within each comparison unit (e.g., countries) and (ii) the superpopulation of comparison units themselves. Thus, researchers need to define such a superpopulation (a population of populations) to complete the theoretical estimand. However, this is—thus far—rarely done in practice, and comparison-unit selection is often driven by data availability rather than theoretical reasoning. An explicit and well-justified definition of the superpopulation from which comparison units are sampled could further help counter the dominance of WEIRD (Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, Democratic; Henrich et al., 2010) population samples in comparative research (Deffner et al., 2022) and strengthen the external validity of comparative inferences.

A second promising avenue for further advancing this methodological framework is the integration of rigorous causal reasoning. This would force researchers to articulate explicit causal assumptions about the data-generating process and to diagnose distinct sources of bias causing non-comparability across units that may invalidate comparative inferences. Recent approaches to survey inference draw on the structural causal modeling (SCM; Pearl, 2009; Pearl et al., 2016), particularly DAG-based (directed acyclic graph; for a non-technical overview, see Rohrer, 2018) representations and the machinery of do-calculus, to derive identification conditions for the theoretical estimand of interest. Applications include the representation of sample selection and missing-data mechanisms at unit- and item-level (e.g., Bareinboim et al., 2014; Elwert & Winship, 2014; Mohan & Pearl, 2021; Schuessler & Selb, 2025; Thoemmes & Mohan, 2015), measurement error and mismeasurement (e.g., van Bork et al. 2024; Pearl, 2012), and questions of external validity covering generalizability and transportability (e.g., Bareinboim & Pearl, 2013; Pearl & Bareinboim, 2014).[3] Latest contributions extend this causal approach already to the comparative case, focusing on measurement comparability (e.g., Sterner et al., 2024, 2026) and cross-cultural generalizability (Deffner et al., 2022). Accordingly, a key objective of the methodological framework for valid comparative inference proposed here is to synthesize these currently disparate strands into a unified comparative approach that causally reconstructs the survey life-cycle model and its comparative extension shown in Figures 1 and 2.

Summing up, this special issue is intended as an opportunity to contribute to an extended methodological framework for survey-based comparative research by bringing together a range of existing approaches. In doing so, it places particular emphasis on measurement-related challenges, which have been the subject of intense debate in recent years (for an excellent overview, see Fischer et al., 2025)—arguably in part because a rigorous and integrative framework is still missing.

Endnotes

[1] While reflective measurement models assume that item responses are manifestations of an underlying latent trait, formative models posit that the indicators jointly constitute the construct (e.g., income, occupational status, and educational attainment as constituents of socioeconomic status).

[2] Note, however, that while these statistical models provide empirical support for a measurement structure, they cannot definitively prove that the underlying assumptions hold. Rather, they serve as a means of falsification, allowing researchers to identify misfits between the hypothesized theoretical structure and the observed data.

[3] Measurement-model construction grounded in rigorous causal reasoning would also elucidate the rationale for choosing between reflective and formative specifications and discourage researchers from selecting either approach for pragmatic reasons (e.g., Bratt, 2025).

References

- Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2014). Multiple-Group Factor Analysis Alignment. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 21(4), 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.919210

- Bareinboim, E., & Pearl, J. (2013). A General Algorithm for Deciding Transportability of Experimental Results. Journal of Causal Inference, 1(1), 107–134. https://doi.org/10.1515/jci-2012-0004

- Bareinboim, E., Tian, J., & Pearl, J. (2014). Recovering from Selection Bias in Causal and Statistical Inference. Proceedings of the Twenty-Eighth AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. Technical Report, R-425, 2410–2416.

- Benítez, I., van de Vijver, F., & Padilla, J. L. (2022). A Mixed Methods Approach to the Analysis of Bias in Cross-Cultural Studies. Sociological Methods & Research, 51(1), 237–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124119852390

- Bratt, C. (2025). Benefits from a Pragmatic Approach: Rethinking Measurement Invariance and Composite Scores in Cross-Cultural Research. Sociological Methods & Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241251405869

- Bollen, K. A. (2002). Latent Variables in Psychology and the Social Sciences. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 605–634. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135239

- Bollen, K. A., & Bauldry, S. (2011). Three Cs in Measurement Models: Causal Indicators, Composite Indicators, and Covariates. Psychological Methods, 16(3), 265–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024448

- Bollen, K., & Lennox, R. (1991). Conventional Wisdom on Measurement: A Structural Equation Perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 110(2), 305–314. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.2.305

- Campbell, D. T., & Fiske, D. W. (1959). Convergent and Discriminant Validation by the Multitrait-Multimethod Matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 56(2), 81–105. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046016

- Collins, J., Hall, N., & Paul, L. A. (Eds.) (2004). Causation and Counterfactuals. MIT Press.

- Conger, A. J. (1980). Maximally Reliable Composites for Unidimensional Measures. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 40(2), 367–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/001316448004000213

- Cronbach, L. J., & Shapiro, K. (1982). Designing Evaluations of Educational and Social Programs. Jossey-Bass.

- Davidov, E., Schmidt, P., & Schwartz, S. H. (2008). Bringing Values Back In: The Adequacy of the European Social Survey to Measure Values in 20 Countries. Public Opinion Quarterly, 72(3), 420–445. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfn035

- Deffner, D., Rohrer, J. M., & McElreath, R. (2022). A Causal Framework for Cross-Cultural Generalizability. Advances in Methods & Practices in Psychological Science, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/25152459221106366

- Dong, Y., & Dumas, D. (2020). Are Personality Measures Valid for Different Populations? A Systematic Review of Measurement Invariance Across Cultures, Gender, and Age. Personality & Individual Differences, 160, 109956. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.109956

- Durkheim, É. (1982) [1895]. The Rules of Sociological Method. Free Press.

- Edwards, J. R., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2000). On the Nature and Direction of Relationships between Constructs and Measures. Psychological Methods, 5(2), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.5.2.155

- Elwert, F., & Winship, C. (2014). Endogenous Selection Bias: The Problem of Conditioning on a Collider Variable. Annual Review of Sociology, 40, 31–53. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043455

- ESS Sampling Expert Panel (2016). Sampling Guidelines: Principles and Implementation for the European Social Survey. ESS ERIC Headquarters.

- Findley, M. G., Kikuta, K., & Denly, M. (2021). External Validity. Annual Review of Political Science, 24, 365–393. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-polisci-041719-102556

- Fischer, R., Karl, J. A., Luczak-Roesch, M., & Hartle, L. (2025). Why We Need to Rethink Measurement Invariance: The Role of Measurement Invariance for Cross-Cultural Research. Cross-Cultural Research, 59(2), 147–179. https://doi.org/10.1177/10693971241312459

- Groves, R. M., Fowler, F. J., Couper, M., Lepkowski, J. M., Singer, E., & Tourangeau, R. (2009). Survey Methodology. Wiley.

- Harkness, J. A. (2003). Questionnaire Translation. In J. A. Harkness, F. J. R. de van Vijver, & P. P. Mohler (Eds.), Wiley Series in Survey Methodology. Cross-Cultural Survey Methods (pp. 35–56). Wiley.

- Henrich, J., Heine, S., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). Beyond WEIRD: Towards a Broad-Based Behavioral Science. Behavioral & Brain Sciences, 33(2-3), 111–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X10000725

- Kane, M. T. (2013). Validating the Interpretations and Uses of Test Scores. Journal of Educational Measurement, 50(1), 1–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jedm.12000

- Kim, E. S., Cao, C., Wang, Y., & Nguyen, D. T. (2017). Measurement Invariance Testing with Many Groups: A Comparison of Five Approaches. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 24(4), 524–544. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1304822

- Kohn, M. L. (1987). Cross-National Research as an Analytic Strategy. American Sociological Review, 52(6), 713–731. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095831

- Leitgöb, H., Seddig, D., Asparouhov, T., Behr, D., Davidov, E., De Roover, K., Jak, S., Meitinger, K., Menold, N., Muthén, B., Rudnev, M., Schmidt, P., & van de Schoot, R. (2023). Measurement Invariance in the Social Sciences: Historical Development, Methodological Challenges, State of the Art, and Future Perspectives. Social Science Research, 110, 102805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2022.102805

- Leitgöb, H., Seddig, D., Schmidt, P., Sosu, E., & Davidov, E. (2021). Longitudinal Measurement (Non)Invariance in latent Constructs. In A. Crenat, & J. W. Sakshaug (Eds.), Measurement Error in Longitudinal Data (pp. 211–257). Oxford University Press.

- Lesko, C. R., Buchanan, A. L., Westreich, D., Edwards, J. K., Hudgens, M. G., & Cole, S. R. (2017). Generalizing Study Results: A Potential Outcomes Perspective. Epidemiology 28(4), 553–561. https://doi.org/10.1097/EDE.0000000000000664

- Lomazzi, V. (2017). Testing the Goodness of the EVS Gender Role Attitudes Scale. Bulletin of Sociological Methodology/Bulletin De Méthodologie Sociologique, 135(1), 90–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/0759106317710859

- Lord, F. M. (1980). Applications of Item Response Theory to Practical Testing Problems. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Lord, F. M., & Novick, M. R. (1968). Statistical Theories of Mental Test Scores. Addison-Wesley.

- Lundberg, I., Johnson, R., & Stewart, B. M. (2021). What Is Your Estimand? Defining the Target Quantity Connects Statistical Evidence to Theory. American Sociological Review, 86(3), 532–565. https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224211004187

- Markus, K. A., & Borsboom, D. (2025). Frontiers of Test Validity Theory: Measurement, Causation, and Meaning (2nd ed.). Multivariate Applications Series. Routledge.

- Meade, A. W., & Lautenschlager, G. J. (2004). A Monte-Carlo Study of Confirmatory Factor Analytic Tests of Measurement Equivalence/Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 11(1), 60–72. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM1101_5

- Meitinger, K. (2017). Necessary but Insufficient: Why Measurement Invariance Tests Need Online Probing as a Complementary Tool. Public Opinion Quarterly, 81(2), 447–472. https://doi.org/10.1093/poq/nfx009

- Menold, N. (2025). Effect of Cognitive Pretests on Measurement Invariance and Reliability in Quality of Life Measures: An Evaluation in Refugee Studies. Social Indicators Research, 179(1), 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-025-03622-w

- Menold, N., Hadler, P., & Neuert, C. (2025). Improving Cross-Cultural Comparability of Measures on Gender and Age Stereotypes by Means of Piloting Methods. Sociological Methods & Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241241307600

- Meredith, W. (1993). Measurement Invariance, Factor Analysis and Factorial Invariance. Psychometrika, 58(4), 525–543. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294825

- Messick, S. (1989). Meaning and Values in Test Validation: The Science and Ethics of Assessment. Educational Researcher, 18(2), 5–11. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X018002005

- Meuleman, B., Davidov, E., & Seddig, D. (2018). Comparative Survey Analysis – Comparability and Equivalence of Measures. methods, data, analyses, 12(1), 3–6.

- Meuleman, B., Żółtak, T., Pokropek, A., Davidov, E., Muthén, B., Oberski, D. L., Billiet, J., & Schmidt, P. (2023). Why Measurement Invariance is Important in Comparative Research. A Response to Welzel et al. (2021). Sociological Methods & Research, 52(3), 1401–1419. https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241221091755

- Mohan, K., & Pearl, J. (2021). Graphical Models for Processing Missing Data. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 116(534), 1023–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2021.1874961

- Muthén, B. O. (2002). Beyond SEM: General Latent Variable Modeling. Behaviormetrika, 29(1), 81–117. https://doi.org/10.2333/bhmk.29.81

- Muthén, B., & Asparouhov, T. (2012). Bayesian Structural Equation Modeling: A More Flexible Representation of Substantive Theory. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 313–335. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026802

- Pearl, J. (2009). Causality. Models, Reasoning, and Inference. Cambridge University Press.

- Pearl, J. (2012). The Causal Foundations of Structural Equation Modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling (pp. 68–91). Guilford Press.

- Pearl, J., & Bareinboim, E. (2014). External Validity: From Do-Calculus to Transportability Across Populations. Statistical Science, 29(4), 579–595. https://doi.org/10.1214/14-sts486

- Pearl, J., Glymour, M., & Jewell, N. P. (2016). Causal Inference in Statistics: A Primer. Wiley.

- Pokropek, A., Davidov, E., & Schmidt, P. (2019). A Monte Carlo Simulation Study to Assess The Appropriateness of Traditional and Newer Approaches to Test for Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 26(5), 724–744. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2018.1561293

- Rammstedt, B., Beierlein, C., Brähler, E., Eid, M., Hartig, J., Kersting, M., Liebig, S., Lukas, J., Mayer, A.‑K., Menold, N., Schupp, J., & Weichselgartner, E. (2015). Quality Standards for the Development, Application, and Evaluation of Measurement Instruments in Social Science Survey Research (RatSWD Working Papers No. 245). RatSWD. http://www.ratswd.de/dl/RatSWD_WP_245.pdf

- Raykov, T. (2023). Scale Construction and Development Using Structural Equation Modeling. In R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling (2nd ed., pp. 472–492). Guilford Press.

- Raykov, T., & Marcoulides, G. A. (2011). Introduction to Psychometric Theory. Taylor & Francis.

- Rohrer, J. M. (2018). Thinking Clearly About Correlations and Causation: Graphical Causal Models for Observational Data. Advances in Methods & Practices in Psychological Science, 1(1), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245917745629

- Saris, W. E., & Andrews, F. M. (2004). Evaluation of Measurement Instruments Using a Structural Modeling Approach. In P. P. Biemer, R. M. Groves, L. Lyberg, N. A. Mathiowetz, & S. Sudman (Eds.), Measurement Errors in Surveys (pp. 575–597). Wiley.

- Saris, W. E., & Gallhofer, I. N. (2014). Design, Evaluation, and Analysis of Questionnaires for Survey Research (2nd ed.). Wiley.

- Schuessler, J., & Selb, P. (2025). Graphical Causal Models for Survey Inference. Sociological Methods & Research, 54(1), 74–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241231176851

- Schwartz, S., Breyer, B., & Danner, D. (2015). Human Values Scale (ESS). Zusammenstellung sozialwissenschaftlicher Items und Skalen (ZIS). https://doi.org/10.6102/zis234

- Seddig, D., & Leitgöb, H. (2018a). Approximate Measurement Invariance and Longitudinal Confirmatory Factor Analysis: Concept and Application with Panel Data. Survey Research Methods, 12(1), 29–41. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2018.v12i1.7210

- Seddig, D., & Leitgöb, H. (2018b). Exact and Bayesian Approximate Measurement Invariance. In E. Davidov, P. Schmidt, J. Billiet, & B. Meuleman (Eds.), Cross-Cultural Analysis: Methods and Applications (2nd ed., pp. 553–579). Routledge.

- Shadish, W. R., Cook, T. D., & Campbell, D. T. (2002). Experimental and Quasi-experimental Designs for Generalized Causal Inference. Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Stegmueller, D. (2011). Apples and Oranges? The problem of Equivalence in Comparative Research. Political Analysis, 19(4), 471–487. https://doi.org/10.1093/pan/mpr028

- Sterner, P., Pargent, F., Deffner, D., & Goretzko, D. (2024). A Causal Framework for the Comparability of Latent Variables. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 31(5), 747–758. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2024.2339396

- Sterner, P., Pargent, F., & Goretzko, D. (2026). Don’t let MI be Misunderstood: A Causal View on Measurement Invariance. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 10, 100261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cresp.2025.100261

- Thoemmes, F., & Mohan, K. (2015). Graphical Representation of Missing Data Problems. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 22(4), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2014.937378

- Uchida, Y., Norasakkunkit, V., & Shinobu, K. (2004). Cultural Constructions of Happiness: Theory and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Happiness Studies, 5(3), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-004-8785-9

- van Bork, R., Rhemtulla, M., Sijtsma, K., & Borsboom, D. (2024). A Causal Theory of Error Scores. Psychological Methods, 29(4), 807–826. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000521

- van de Schoot, R., Kluytmans, A., Tummers, L., Lugtig, P., Hox, J., & Muthén, B. O. (2013). Facing Off with Scylla and Charybdis: A Comparison of Scalar, Partial, and the Novel Possibility of Approximate Measurement Invariance. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 770. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00770

- van de Vijver, F. J. R. (2018). Capturing Bias in Structural Equation Modeling. In E. Davidov, P. Schmidt, J. Billiet, & B. Meuleman (Eds.), Cross-Cultural Analysis: Methods and Applications (2nd ed., pp. 3–43). Routledge.

- van de Vijver, F. J. R., & Poortinga, Y. H. (1997). Towards an Integrated Analysis of Bias in Cross-Cultural Assessment. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 13(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.13.1.29

- Welzel, C., Brunkert, L., Kruse, S., & Inglehart, R. F. (2023). Non Invariance? An Overstated Problem With Misconceived Causes. Sociological Methods & Research, 52(3), 1368–1400. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124121995521

- Wu, A. D., Li, Z., & Zumbo, B. D. (2007). Decoding the Meaning of Factorial Invariance and Updating the Practice of Multi-group Confirmatory Factor Analysis: A Demonstration with TIMSS Data. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 12(3).

- Yoon, M., & Millsap, R. E. (2007). Detecting Violations of Factorial Invariance Using Data-Based Specification Searches: A Monte Carlo Study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 435–463. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301677

- Zumbaro, B. D., & Chan, E. K. H. (2014). Reflections on Validation Practices in the Social, Behavioral, and Health Science. In B. D. Zumbo & E. K. Chan (Eds.), Validity and Validation in Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences (pp. 351–357). Springer International Publishing.